UNDERSTANDING BITS

UNDERSTANDING BITS

Walking into a saddle shop and looking at a wall covered with bits can send a neophyte bit buyer into a cold sweat. It is embarrassing to tell the salesperson, who often look like they just won the national reining finals, that all we know about bits is that they are supposed to turn the horse left, right, and ‘whoa’.

Take another look, it is not so bad. We can simplify types of bits and put them into two categories, snaffle bits and curb bits. The snaffle bit has no shank or lever on the side of the mouthpiece. Rather, it has a round ring, a ‘D’ shaped ring, or some other flat side on the ring to prevent it from slipping through the horse’s mouth when we apply direct pressure (directly pulling the head around). The reins are attached to the ring. Snaffle bits often have a jointed mouthpiece, which is friendlier and generally applies less pressure than a solid mouthpiece.

A curb bit has a shank or lever on each side. Regardless of whether or not a curb bit has a solid or a jointed mouthpiece it is still called a curb bit. The reins are attached to the ends of the lever and when pulled the lever swings back and as the chin strap tightens it applies a nutcracker effect (which is why you need a chin strap with curbed bits). The mouthpiece and the curved bump or ‘port’ of the mouthpiece applies pressure to the tongue, roof of the mouth, and bars of the mouth. The longer the shanks the more pressure is applied. On a moderate length shank when you apply five pounds of pressure in the reins, about fifteen is applied to the mouth. The purpose of having the curve (port) drive up and touch the roof of the mouth is to ‘cue’ the trained horse for the desired response.

Three eights of an inch is a standard thickness for the mouthpiece. Thinner mouth pieces, for example a one quarter inch twisted wire bit, are simply too harsh and can damage the horse’s mouth. We have some training bits that are thicker than three eights but I feel that on a trained horse more thickness in not necessary and takes up more room in the horse's mouth, reducing comfort. The first time our horses are under bit we often use a thicker bit, sometimes a rubber bit, until they are comfortable with the feel.

It is important to note that when using a bit for early training you need to use a snaffle bit as you are applying direct pressure. Do not progress to a curb or shanked bit until the horse is responding to indirect pressure (neck reining) and body cues. This means that the horse is calm and responds softly to cued stops, lateral flexion, flexion while riding in circles, riding straight between the reins, and backing up. Direct pressure applied on a curb bit will twist the bit in the horse’s mouth and compound confusion and pain. Using a curb bit will not help train a green horse for the above requests, proper training will. It is extremely important that the horse’s frame of mind is soft and accepting before using any bit, meaning you need to have achieved join up, respect, and soft responses when applying pressures.

Trail riders often ask, “Why can’t I just use a snaffle on my horse all of the time?” You can, and many riders do. All you should really need to direct your horse is a piece of string for reins and body and leg pressure. The reason that many trail riders and trail riding operations use a curb bit is primarily for control and safety. There are situations that can develop on the trail that may require control in difficult and heated circumstances. Horses can become spooked, irrational, and defy their riders, and a curb bit simply offers more control and safety in these difficult moments. Does this mean that you should use a longer shank and a mouthpiece with a high port, like a spade bit for example, to increase control on a difficult horse? Absolutely not. Extreme ports are for riders riding well trained horses and applying very subtle cues to get a desired response. If your trail horse is defying you it has other issues like a lack of respect, a high maintenance personality, and a need for more training time in a controlled environment like a round pen or a lunge line.

You need to go back to basic training for unruly and stiff horses, not a more extreme bit or a mechanical hackamore. Early training and problem solving is best done with a snaffle because they apply less pressure, not more, and you need your horse to ‘want’ to respond softly to simple, light pressure, not pain from an aggressive bit. Choosing the right bit is important, but choosing proper training and using the bit properly is more important.

It is very important that trail riders cue their horses with bumps or pulses from early training onward as it will allow the rider to communicate and correct the horse with firm bumps then lighten up with soft pulses as the horse understands and provides the desired response. This carries on to trail situations when a horse gets pushy and wants to pass other horses or does not listen to your cues, and you need to check the horse aggressively with bumps, then lighten up as the horse responds. Riders who are not communicating with body language like leg pressures and only using bit pressures to cue horses simply do not understand horses.

Bits vary in materials and quality. Avoid aluminum and cheap plated mouth pieces as they do not encourage salivation or taste good to the horse. Iron or copper or a combination of both is considered most desirable. You often hear the words ‘sweet iron’ used as the most desirable material for bits. Some describe sweet iron as common black iron with carbon added as a hardener and others have described it as an iron/copper alloy. Either is very good. Because of the number of horses, we use I settle for an iron or a copper mouthpiece and do not worry about the ‘sweet’ part, and we do not worry about some rust on our iron bits that have sat for some time as horses have no issues with rust, some believe that they even enjoy it. Stainless steel is a common material used in mouth pieces as it is very durable and long lasting. It is ok but does not encourage salivation and is not as pleasing to the horse. Copper generally has some nickel or other metal added as an alloy for a hardener.

All things considered our experienced horses generally carry a medium shank, medium port curb bit, as with many trail riding operations. We are conscious of the width of the bit so that it is not narrow and pinching the mouth and not wide and sloppy. It is adjusted in the head stall so that it just contacts the corners of the mouth, so that the horse carries or packs the bit and so that that there is not two or three wrinkles in the corner of the mouth but one wrinkle or no wrinkles. The chin strap is adjusted so that when not in use you can slip the width of two fingers between the jaw and the strap. There is really no need for a very aggressive chain on a chin strap but a nonaggressive chain or leather is just fine. A chin strap on a snaffle bit serves no functional purpose except that on the trail, if you need to force the horses head around, say to disengage the rear quarters of the horse who is on a runaway, the chin strap helps prevent the snaffle from sliding through the horse’s mouth.

True hackamores are wonderful for both training and trail riding, but they are a separate science and need to be studied before you use them. They vary in construction and quality, need to be adjusted properly, and encourage horses to become stiff if not used properly. For a few years I used a short shanked curb bit with a jointed mouth piece commonly called a Tom Thumb. I believed, like many, that they were gentle in the mouth because of the jointed mouthpiece but discovered that a single jointed mouthpiece drives up into the roof of the mouth when the shanks are engaged. A double-jointed mouthpiece, with a ball or a roller in the middle is gentler, if that is what you really need.

You often see rollers in the mouthpiece of bits. Their job is to provide entertainment, maybe some activity to occupy or calm the horse, and to encourage salivation. They are not intended to increase or decrease the severity of the bit and if I happen to have one, I will use it but see no real advantage, and at times a horse who constantly fusses with one may be a bit of a nuisance.

Bits and bridles are systems and systems are not perfect in all circumstance. Trail riders are not perfect either and conditions on the trail can be far from perfect. Even though you are not supposed to plow rein or apply direct pressure on a curb bit there are times in the life of a trail rider when you will. Maybe the horse bolts and turning it is critical to prevent a run away, maybe the trail is eroded and drops off or maybe the trail suddenly becomes dangerous for a number of reasons and you have to halt even when others do not, and so you end up reefing on your bit as a matter of survival. Suddenly the calmness, disposition, and training of your trusty trail companion shines through, or, lets you down, and maybe not gently. In unexpected times I have ridden many miles with nothing but a string for reins and a rope halter for a headstall, and with no difficulty, but shudder in my gum boots at the thought of doing it with a high-strung horse. Walk a mile in my stinky old Value Village gum boots and you will understand.

Happy trails!

After round pen training and join-up, the mouth bar of the first snaffle you use needs to have decent thickness. We prefer rubber mouth pieces as young horses can chew on it and get comfortable. Give them a few hours to accept the bit, feed them treats, have them join-up again, before you apply pressures.

A medium port, medium shanked bit is a good bit to use. This bit is tough stainless on the shanks but an iron or sweet iron mouth bar – good taste and great for the salivation you want to create.

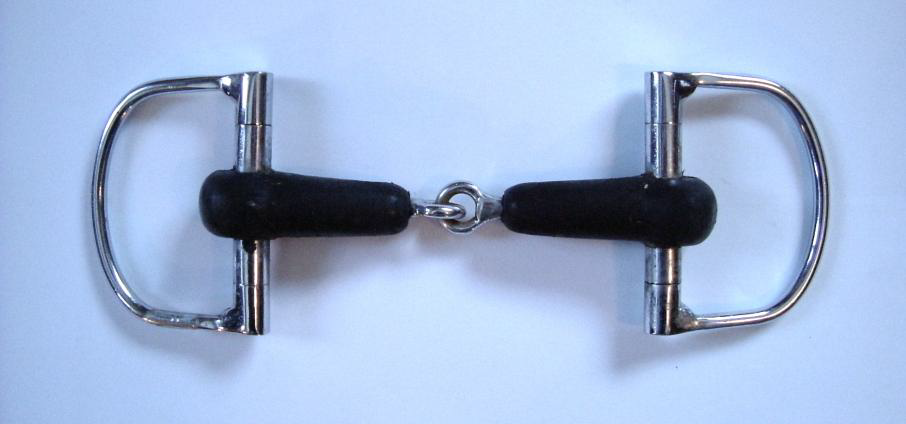

We prefer a D ring or egg butt snaffles as opposed to 0 ring, as they are less likely to slide through the mouth with direct pressure. Like iron, this copper mouth bar encourages saliva.

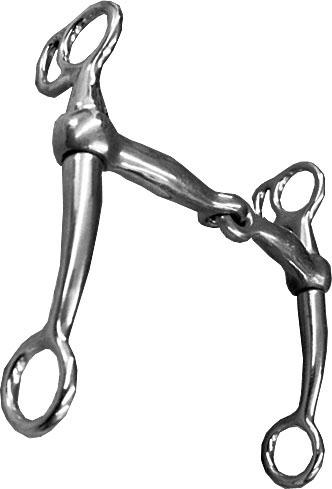

Shanked bits are called shanked bits (or curb bits) even if they have a broken mouthpiece. They are snaffles only when they have no shank. This Tom Thumb snaffle appears friendly as it has short shanks and a broken mouthpiece. It’s not friendly! When reins pull on the shanks the mouthpiece rises up as a sharp wedge against the roof of the mouth.

If all your early training and riding is with a bit, it needs to be a snaffle bit as you will be using direct pressure. Never switch to a shanked bit until the horse is responding to cues properly, meaning indirect pressure with reins

(neck reining), as well as leg pressure (cues). Applying direct pressure on a shanked bit torques it and hurts the mouth as well as confusing your request.

Riders often wonder why anyone needs to use a shanked bit at all, why not just stay with a snaffle? – You can, and many do, including ourselves, more so as the years went by. However, for trail riding the curb bit offers more control in the case of a runaway or a difficult horse that needs to be ‘reined in’ in the case of an emergency. I have heard that some insurance companies and some States require commercial horse-riding operations to use curb bits exclusively. Also, the reason that most outfitters have traditionally used basic medium port, medium shanked, iron curb bits.