ONE TOUGH DAY

ONE TOUGH DAY

I am a trail riding dinosaur, and proud of it. If you began your trail riding in the sixties and seventies, or earlier, you did not have cell phones, GPS, SPOT, Google Earth, SAT phones, and likely never used a two-way radio. You could not sit at home with your lap top and zoom in to your house, or focus on the numbers of your license plate, or a horsefly on your horse’s butt. These days, if you are like many, you find yourself saying ‘wow’ isn’t that great’ every time some wonderful new technology comes along. Well, ok, you are right, wonderful technology comes along with just about every full moon.

I believe, for a few good reasons, that the technological world is at odds with mother nature, and the joy of trail riding the wilds.

When you go out for a few hours or a day or a week you truly want to separate yourself from the worries and stresses of life and civilization. You want things simple - you and your horse and the trail and the skies and the sun and the trees. I promise you that the quality and sense of the adventure will not be the same if you just must make that phone call, or you are waiting for one, or you call you buddy every few minutes on the two-way to see if things are ok.

I remember one fine day on a remote mountain top with a friend. We worked hard climbing to alpine and we shared wild and remote feelings about the alpine basin we discovered, and a herd of beautiful caribou that frolicked about – and then out of the blue comes this booming voice on the walkie talkie we were told to carry, “How you guys doing! Where you at! Give me a call! Over.”

We felt robbed, the precious day stolen.

The worries that you have in your life you had well before you headed out on the ride. During the ride worries melt away because you feel connected with your horse and the natural world, not because you carry gadgetry. Many have been brainwashed thinking they cannot have a safe ride without a half dozen gadgets welded to them or their horse. Serious injury on trail rides is rare, death very rare, and I doubt that a sat phone will help a drowning in a river or a knock on the head. although it may get one to medical attention sooner. I am not saying a boat on the high seas should not have radar and GPS and a Sat phone, I am just saying it does not make your trail ride more enjoyable or adventurous. And there is the key word. Adventure!

Some may want their trail ride canned and wrapped, knowing where every trail goes, what’s around the bend, and how long it takes to get there. I don’t. I want it to be a surprise. I want it natural, and I want to deal with what is natural and real. Trails are trails, what fork you take and what lies ahead is the fun of it, the challenge, what makes one feel free and alive. There is a deep satisfaction of being one with your horse, your natural surroundings and knowing and feeling, at least little, of what Daniel Boone and Davey Crockett felt. If I pick a dozen of the most memorable moments, memorable days, from a hundred adventures in the wilderness, not one would have been enhanced by technology or being guided along the trail.

Memorable times on the trail can be good, bad, and ugly, just like life, so a breathtaking view, a smile on someone’s face, a close call, and hardship, is all part of what keeps it real, and I would not trade having lived it for anything. And speaking of hardship. It is inherent, and it comes in many shapes and sizes.

Let me share the longest, toughest day on the trail I have known. It was a slice of the CORDILLERA! Adventure - over a thousand wilderness miles across the North American mountain system, from the plains to the pacific. It happened about thirty days in, after endless days of deadfall, bog, crippling fatigue. In my memory this day was one of many that ran together like an exhausted nightmare of misery and suffering. I assure you it was much harder on us humans than the horses, who had great feed each evening, night and morning, and got to stand around while we suffered, deeply, trying to cut and push through scrambled, broken, mountain wilderness ………..

……….Three times my eyes opened but each time it remained dark, the stars gone, the sky a little less black, slowly turning gray as the ground.

“I guess we should wake Stan,” someone said.

“Well, I’ll go after the horses.”

“Why not eat first. I’ll go with you. It’ll take both of us to catch that brown bugger.”

“Even the pinto’s been hard to catch lately. Salt doesn’t work.”

“You’d think they’d be too tired to run away anymore.”

“Who needs it.”

I tried to lift myself up but the cobwebs that enveloped me pulled me back down. Brian and Bill heard my movements.

“Getting time to go,” someone said.

Tick me off. I forced myself to one elbow. “What’s going on?” I could not see their faces, but I guessed no one was smiling.

“Nothing’s going on, it's time to go.”

“Time to go!” I barked. “We didn’t go to bed till probably midnight. It can’t be four yet, its still dark, what are you doing?”

“For crying out loud,” Bill fought back. “We’re two weeks behind. You’re the one with the high flyin’ ideas; travel like an army, can’t waste time, get going by eight every morning or we’ll lose two hundred miles by September, or maybe you forgot?”

“No, I didn’t forget, what do you want me to say, I’m wrong? Ok, I’m wrong, I was wrong. We knew a week after we left that I was wrong. What’s the point in killing ourselves over it?”

“Oh c’mon,” Bill poked at me. “You think you’re the only one it’s been hard on? Brian has lost ten or fifteen pounds, and I’ve probably lost twenty and there is no way we can even hope of reaching Stewart at this rate. The last four days you can cover how far we traveled on map with a fingernail. Let’s just get going to Fort Ware.”

Brian cut in. “If we’re not at Fort Ware by the thirteenth, Ilene is supposed to call the RCMP. We’re already late.”

“Late for what,” I mumbled to myself.

I pulled my legs from the sleeping bag. Something held my foot, my sock was stuck. I pulled my leg. My foot hurt. I folded back the sleeping bag. My sock was stuck to the bag. Blood. I carefully peeled off my sock. It hurt. My big toe was stuck to the inside of the sock. I tugged at the sock and it came loose with a sharp pain. My toenail just hung there, stuck to the sock with dried blood.

It was no use. All I could hope for was to sleep on the trail. I stood up and was swept over by dizziness, staggered like a drunk, fought the dizzy spell. I was punch drunk from fatigue and the day had not even started! How could I survive another day.

We plodded weary steps down the trail. The invigorating chill of the dawn attempted to pry open my eyelids but lost the battle. Up against a twisted tangle of fir Brian pulled his axe and chopped away. I wrapped Lucky’s and the packhorses leads around a log then lay down and passed out.

A couple of hours passed by, and the morning sun climbed high and its heat beamed me awake. “Ohhhh…” I pulled myself up, rubbing needles and leaves from the impressions they had dented in my cheek. Lucky swished his tail at a horde of period sized sand flies. There was only one type of fly, but we cursed them as sand flies, black flies and no-see-ums. I rubbed my chest smartly then inspected the hundred tiny red welts. The little buggers just crawled into our clothes and sleeping bags and helped themselves.

Two hours I had passed out, and now I walked to find the other horses up ahead - seventy yards ahead, stuck in the mess. Bill and Brian fumbled along, cutting at the tangles of alder that harassed our every step and bounced back with each blow of the axe. I fell into place then took my turn with the axe, one of several bouts in rotation. Twice we hauled through muddy channels of dead water and twice we had to re-pack the horses.

We decided to head from the river into the forest, in a direct south line, hoping to cut off a six-mile loop of the river. At first the decision appeared wise, but it was a brief victory for our beaten outfit. Without warning we found ourselves picking paths along dry humps of land between sloughs and channels of dead water that swamped the ankles of willow bushes. The Douglas fir trees were enormous, many as fallen monarchs laid on their side as wide as we were tall. There was no stepping over these fallen soldiers. Worse, every time a tree fell the uprooted roots left a hole that could swallow a horse. There was not much ground left for man or beast. It was nature’s creation of a mine and mortar bomb field, and we suffered our greatest vexation yet.

Time and again we slugged through shallows. Slop, slop, slop, slop. Drenched socks squished in soggy boots. The horses stole bits of tall swamp grass. Again and again, we were forced to stop. We drew energy from reserves deep within, beyond what we believed possible. We were forced to fan out to find possible routes, and then were forced into impossible routes where we reefed horses out of holes. By mid-evening the fortitude that we had drawn freely from for so many days could no longer supply our demands, no matter how frequent the rests, no matter how much cold water we drank, and no matter how often we maddened ourselves for shots of adrenalin. Our faces lingered permanent contortions of stress, filth and defeat.

Repeatedly, again and again, we stumbled and fell, stumbled and leaped, leaped out of the way of the horses who jumped for firm ground on our heels and backsides. And now, in the graveyard twilight of the tombstone ridden forest, even the horses stumbled under the packs, with no hope of solid ground. The horses stood at odd angles, legs in and out of branches, sinkholes, moss, and bent willow.

There were no birds with pretty voices. Sunshine robbed by towering mountains leaving a dark canopy. Worst of all there was no hope for improvement. It was the closest place on the natural earth that I had ever known, or would ever know, to an imagined hell. Two horses lay down, uncaring of the human threat that normally accompanied the act of quitting. I dipped my hand into a black water sinkhole, the pain from busted blisters meaningless and insignificant.

Bill's eyes watered and I believe he held the tears of defeat that we all had coming to the surface. If the black dragon of death cried over our heads now, we would not have had the energy to loose an arrow at it. If we had ever known it was over, no matter how we felt, it was now. Bill and Brian fell to the ground, lay there, Bill finally spoke. “Brian and I……we can’t.” He lifted his forearm against his forehead then it flopped back down.

I had just taken my turn with the axe. It was their turn. I bent my head and crawled inside of myself for the greatest physical battle of my life. “Oh God, where can I find the strength?” I said to myself. I wasn’t ready to die.

In death there would be relief. But now, I could not forgive myself for the hardship we had put upon not only ourselves but the horses. The river’s edge where there was always hard ground and good feed was out there somewhere. There was only one path to forgiveness – keep going toward where the river, somewhere, had to be. To keep cutting appeared inhuman and impossible. This was the final cut, and if so - the last cut is the deepest.

“Where?” I said to Bill, “Which way?”

“I don’t know.”

I crawled to my feet with the help of a log and forced a few steps toward where I thought the river should be. “It’s gotta be there……”

“What if it is. We can’t go on. It’s getting dark…….”

I had never known such complete fatigue. Yet, somehow, to this day, inexplicably, the axe continued to bite with deliberation…..

You cannot know what it meant to finally hear that river.

We all carry the battles, losses, victories of our lives, branded by them, and this moment was the moment that marked us, what held us, beat us, made us crawl, yet defined us.

To survive, to stand again, and be counted.

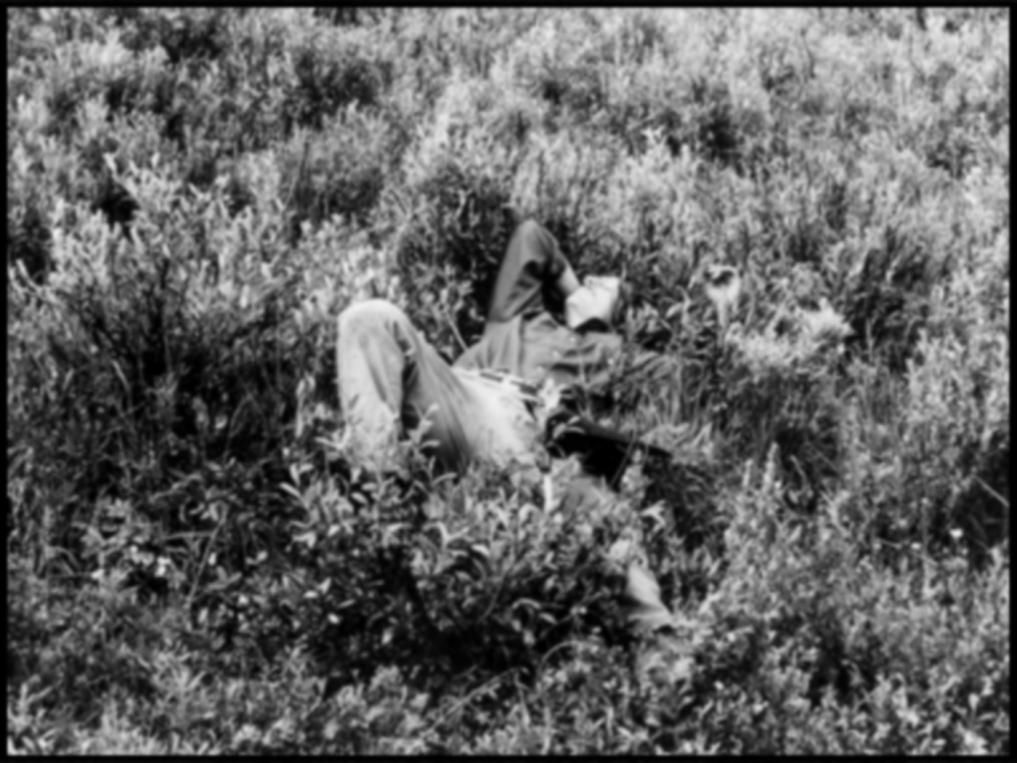

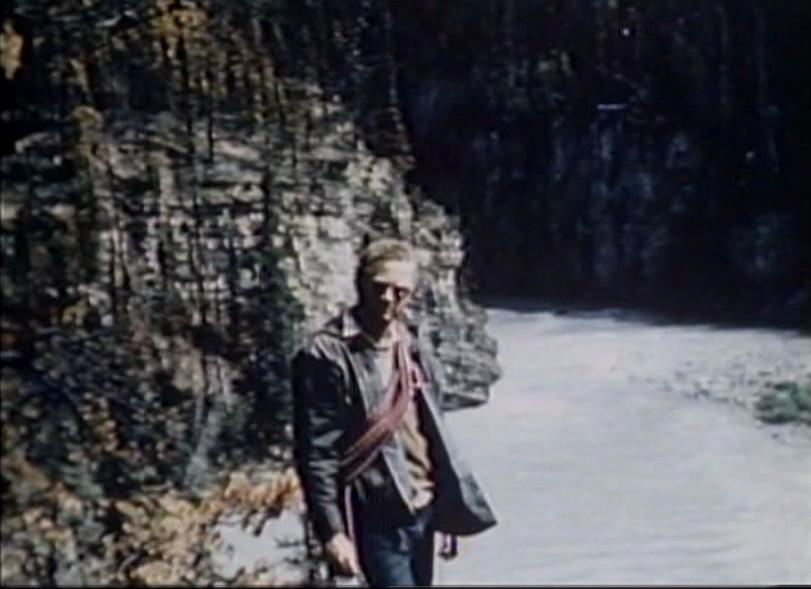

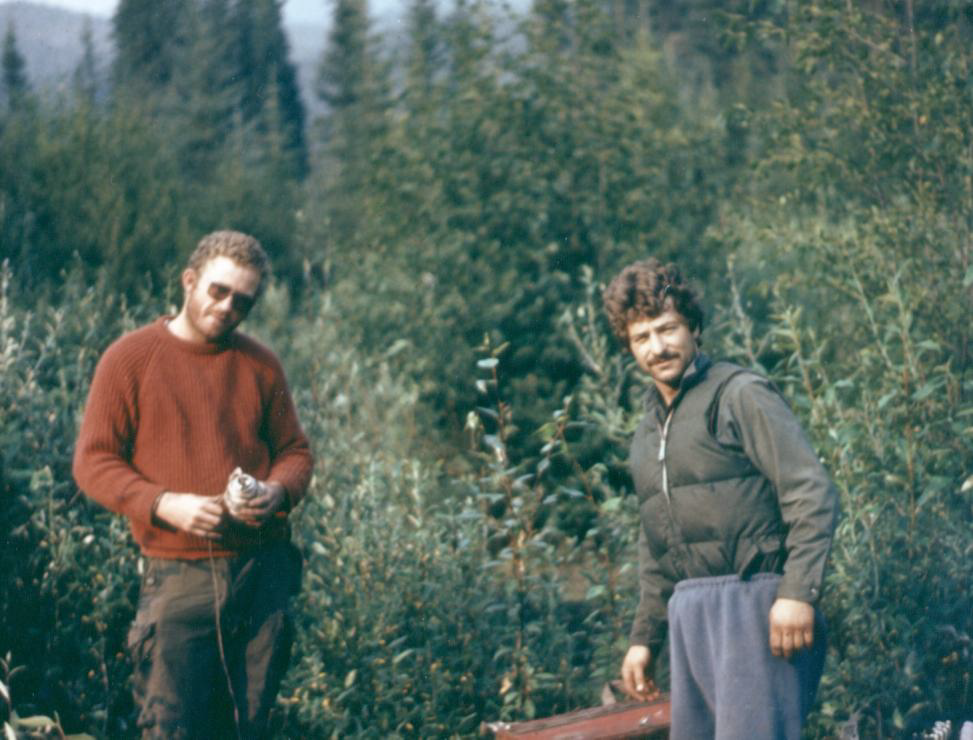

Most of the images below were taken just prior to this ‘One Tough Day’ In reality, it was one tough, or impossible day, day after day after day, for several days. Brian took that photo of me collapsed on the ground. Bill literally went out one morning trying to find a route through cliffs and canyons. The image of Bill and I standing together was taken the morning of the day when my big toenail was stuck to the inside of my sock. I am surprised that Brian had the desire to take photos at all – good for him!