NIGHTMARE ON CARIBOU CREEK

NIGHTMARE ON CARIBOU

CREEK

Do you have a trail riding nightmare? A thought, a fear, an accident that could or did happen? I suppose if you play on adventures doorstep long enough, ride the rough trails year after year, that sooner or later your number will come up. Maybe.

But we have a life to live, people to see, places to go, country to explore. Accidents happen to other people. We read about them in the newspapers.

At least that is how I lived much of my life, as many wilderness riders do, as likely to step aside for fear as a stick on the road. Except, now I have a memory, a haunting memory, a trail riding nightmare. The mere thought of this nightmare brings forth a vision; my wife, daughter and horse, free falling to the boulders below. And after all these years the vision floods me with panic and helplessness, and so it stays, locked away, mentioned rarely. I am not sure why I am telling this story now except that maybe it is time, and there are some lessons here.

We were two long days in. Twenty-five horse miles up the Halfway River and on a good trail, once a cat trail, and fifteen miles up a remote creek, on a rugged trail, when there was a trail, littered with deadfall and washouts, the type of ancient trail you would expect when penetrating wild country looking for undisturbed wildlife. And we were not disappointed. We had seen good numbers of buffalo, moose, several elk, and few caribou.

And now it was time to head out. We had taken a nice bull moose, a full freezer of good eating for the winter. Myself out front with eight-year-old Dylan riding behind me, several packhorses, Marlene and six-year-old daughter Aaron riding double, and Ross trailing. We had made a few miles, mostly following our trail coming in but at times trying easier paths around some logs, around some brush, or across the stream that wound its way down the valley. It was slow going on this obstacle course and I rode rubbernecked, checking the progress of the riders and horses behind.

We rode along a low forested bank of the stream. A small flat opened and then the trail climbed uphill, squeezed between the creek and a steep brushy hill that pinched us bank high against the stream. We edged upward, ten feet or so above the mess of stones and boulders that formed the stream bed. I rode carefully, intent on finding safe passage along the edge of the high bank. We rode slowly along the narrow trail a couple feet wide, the straight drop down on my left, my gut tight as Dylan and I rode over the high point of the bank, then relief as we angled down to a flat on the far side. I held up, turned to watch the pack horses, Marlene and Aaron.

Those fleeting moments of tension, what comes and goes for all wilderness horse travelers; no close calls in a good day but by the week, a month, a lifetime, tight moments in tight places are a fact of life – and when they come, like dark shadows that flood ones chest, then gone, all over, all good, relief, evaporated into nothing, all over but the smiling in the sun.

Or not.

The first two packhorses edged along the narrow path just fine. The third packhorse slowed, nose down, wary of the trail, now churned-up soil at the narrowest point, and the straight drop down. He scrambled, his hard push knocking off a two-foot chunk of black dirt that crumbled and spilled down to the boulders below, one back foot broke through, he slipped then dug in and ran across, over the high point and down to the flat. Then two more packhorses, faithful to a fault yet sensible enough to edge away from the missing chunk of bank they swung a little wide, made their own path, then walked quickly as if the tight squeeze had their guts churning too. In a blink Marlene with Aaron clinging to her backside were at the dirty gap. I wanted to yell, to scream, move the horse over! Or, hold up! But I knew what would happen if I did – the confusion in Marlene, the fear, whose own panic would confuse the horse too, making it worse. And I trusted the horse she rode, Mom, trusty all day long, all life long – a bomb proof kids horse. Solid and reliable only begins to describe how wonderful she was. ‘Stay calm, stay calm’, my mind reeled.

Nose down, straight along, straight along the tracks of the first horses, then a foot slipped into the rotted hole, the bottom dropped out of my gut, please Mom, step to the side!

No, as if deliberate she just seemed to walk into the ruined black gap as if blind. The bottom crumbled out of what was left of the trail, they toppeled……free falling.

Horror crashed against my very being.

“Mom!” Dylan screamed.

Dirt spilled down in a black spray flung over boulders below, over us, over life as we knew it. Gone. Into a nightmare.

Time froze in that horrible moment. The vision forever indelible. The horse, Marlene, Aaron, suspended in air yet free falling, then crashing on the rocks, Myself and Dylan behind me bailing off our horses, Dylan yelling for his mom, both of us racing back.

There was a silent moment when the horse lay on its side, apparently in shock. Marlene and Aaron half under the horse, also silent. The mare began to struggle. Her front feet grappling to find purchase, her hind end laid down sideways. Marlene moaning, Aaron crying. They were alive. And then the mare in a drunken stupor lunged to her feet, swayed as if in a drunken stupor, then collapsed again - on Marlene. She screamed terribly.

Again, the horse regained its footing, steadied herself. Aaron collected herself, crying, helmet busted – please God let her be ok – Marlene moaning, bent and somehow broken among the boulders – please God. We scrambled down the bank and in an instant by her side, her leg at an awful angle from the hip down. I knew her femur was broken. I also knew that if her femoral artery was cut she would soon be in shock and there was nothing we could do.

We needed to get out of the wet boulders, out of the drizzle that began to fall, yet afraid to mover her leg. As careful as possible without disturbing her leg, we gently carried her up the bank keeping her leg from moving as much as possible, all the while Marlenes painful moans cut through us like knives in our hearts.

And now what?

There was no choice in the matter, only one way out, and that was for me to get out, get help. Fast. The thought of leaving Marlene terrified me. What if. What if there was internal bleeding, and this moment our last together, this nightmare that I created - the result of my need to wander the wilderness. Is our last moment together?

On a small flat upon the bank we set up the tent and moved her inside, placing sleeping bags under her and over her, her small cries at every slight movement, I could tell she bravely tried to hold them back, but the pain was just too much.

Marlene was suddenly calm, fatigued I thought, fading, I hoped to God not. Was she fading to sleep, or worse.

“Stay awake,” I said, half moaning myself, then talked to her, louder, barked at her – “Stay awake! You can’t sleep now!” I had heard that a person going into shock needed to stay conscious. So, Ross and I kept at it as we tried to make her comfortable. With the warmth of the sleeping bags, she appeared to settle. She spoke a few words, can’t remember what. We monitored her breathing, steady but shallow. Aaron laid down beside her mom.

I bowed my head against hers. I still feel the moment, pleading, with love, with tears welling, “I’m going for help. Get a chopper. Stay awake, ok, stay awake. Don’t sleep.”

I didn’t say, ‘I love you’ and I don’t know why. Maybe deep guilt – it was I who put her here. I did this. Did this to you, to the kids.

I left the tent.

I had six hours until dark, I had to leave. Quick. Ross would stay and keep her warm and dry and try to keep her conscious.

“Don’t let her sleep!” I ordered. Ross nodded, looking grave, determined, and white faced.

I pulled my saddle off Yukon, the gelding I rode, and threw it on a tall thoroughbred packhorse I had been training as a riding horse. Now a twenty-mile run on a big black thoroughbred cross that could eat up ground in a hurry. I don’t remember much about that run. The miles of rough brush, the twisting stream, just raced by; feelings of desperation, guilt, and yes, deep fear – mixed with prayers. The brush grabbing, tearing at us, meant nothing. The rocky ground, ditched ground, sudden stream banks – nothing. He was the only thoroughbred I’d ever owned, and I will never forget how he ate up the ground.

It seemed forever to the Halfway River trail.

We finally tore out onto the open track then really lit out, the horse and I already sweated up. I pushed him to the limit, the rocking of his long body with long legs and sloped pasterns kept a smoother rhythm than any horse I have owned before or since. At times we slowed to a trot, can’t remember walking but maybe we did. Can’t remember much with the thought of what – what? …….What I had done, to her, to the kids. Please God, please, please…….. Black clouds above, black clouds of doubt in my heart, a roller coaster ride of fear trading places with hope – things will be ok, they must, they just have to. Eyes clear and seeing the road one moment, then blurred with tears the next, can’t see, don’t care.

Mountain slopes and the pretty meadows along the valley that rolled past were pretty no longer. Still ten miles to go to the trail head. We were beginning to tire, deeply, and I knew the willing horse could not keep the pace much longer, even though we slowed to a trot now and then, even walked for a minute of two.

We rounded a slow corner, a brushy meadow on the right.

Wall tents! A hunter’s camp. A quad. Two men stood outside, I turned into the camp, horse lathered. One man turned toward the tent and spoke and a third man stepped out.

“I have a serious problem. My wife’s horse went over a bank. Her leg is broken, badly, I think she’s in shock.”

The three guys looked at each other briefly.

“Get the cell phone. It works here, sometimes.” One of them said.

Oh God I thought. Is this possible? Phone, from here. Middle of nowhere?

It did, barely, through the static was the voice of an operator, then an emergency person.

“Listen, this is serious. My wife is seriously injured 45 miles up a horse trail, up the Halfway River, then up Caribou Creek.”

I described the location in detail. Not complicated. “You need to get someone out here now!”

“Just a moment please.”

A minute later, “We’ll call you back with an ETA.”

“ETA? What?! You need to get out here!”

There was still two hours of daylight remaining.

“We will send an ambulance out as soon as possible. We’ll call you back with an ETA.”

“Ambulance! Are you listening? It’s a horse trail! You need a chopper! Two hours from now is too late!”

“Calm down. We have to go through procedures.”

“Procedures? You’re not hearing a thing I’m saying. It’s a horse trail! You need to get someone in here before dark. Her femur is broken she could die! Do you even hear me? Are you listening?!’

Calm down, if you don’t you can call us back.”

Calm down, calm down!” I was in shock, disbelief.

They passed me on to someone else - what they said - there would be no help coming until a chopper would be sent the next morning. A forty-five minute chopper ride from Ft. St. John!

I was sick. It felt as if they just did not care, not enough, not enough to drop everything in the hope of saving a life. As if they had better things to do. What? Have dinner, watch the Simpsons? I was sick with disgust, worry, anger.

The first, and only time in my life that I did believe I could, and would, kill someone – the person responsible for not coming to save Marlene’s life – if she should die.

“I’m going with you.” A hunter named Louis said. “We’ll tell your wife I’m a doctor. It will give her hope.”

Hope, I thought. Dear God.

“No,” I said, “I can go myself.”

“I’m coming,” he said, and jumped on the quad. “Let’s go.”

We went up the Halfway trail as far as we could on the quad, then I began a foot run through the thick, tangled forest, across streams, in the dark. At times Louis was with me; at times he fell back then had to find me in the dark. Black as night. He was tired and beaten up, but never quit. He gave it his all. A truly good person. Strange how through his courage and kindness he had begun to feel like a friend I had known for ever.

Later, he said he did believe he was going to die of exhaustion.

There was no stopping, driven by the whip of fear, energy from hope, hope that Marlene had not gone into shock. If not, she could make it, I believed it, had too.

We made it. Marlene was breathing, calm, slow, and she was rational. Thankyou God. Thank you, thank you, thank you. Louis told her that he was a doctor and began to ask questions. His impersonation worked, gave Marlene hope, gave all of us hope. Foolish perhaps, but true. He was a tremendous help. Marlene never did know that he was not a doctor, not until 15 years later when I let it slip while telling someone the details of the story.

The coming day took forever, morning slid in grey, wet, and indistinct. The chopper did not show at daybreak, not until three hours later. They got lost, had a hard time finding Caribou Creek, they said.

I will forever despise them for their poor performance. It could have ended much worse. Marlene had a seriously fractured femur, which now has a metal rod in it, and a fracture in her lower skull.

Here is what I know: If there is an eroded bank, a drop off, a tight spot, get off and walk. Remember Murphy’s Law. Ditto for sticks pointing toward you or your horse as you ride down the trail. Get off and move them. They can, and do, spear horses, people, get stuck in stirrups and cinches and cause wrecks.

I believe the riding helmet saved Aaron’s life. Broken like it was, imagine if she did not wear the helmet. And do not rely on a sat phone to save you. You need common sense, and lots of it, if you are to avoid trail problems, escape difficult trails that you absolutely will have to overcome if you are a wilderness horse rider. Take your time, scout for the best passage, don’t rely on good luck – although you will need it.

Postscript:

A year later we walked into a doctor’s office. “What’s wrong with your leg?” He watched Marlene limp in.

“A horse broke it,” I said.

“I don’t think so,” he said.

What is he talking about? I thought.

Why are we here? I wanted to ask. But I held my tongue; he was a heralded brain surgeon.

“Look at this.” He pointed to a computer screen. He scanned up and down. It looked like a vertical cylinder, like a rolling pin, a thick tree trunk with many branches.

“What is it?” I said.

He looked at us oddly.

“It’s your tumor, didn’t you know?” He said to Marlene.

This doctor was, to us, a miracle worker. He removed a non-cancerous tumor, the size of a small grapefruit, which may have been there for many years, we will never know. To this day her brain squeezed against the inside of her skull, the small grapefruit sized hole filled with liquid. Three days after the operation Marlene walked from her hospital bed to the window. The limp was gone. I held my tongue. It was a good time to bury the past…… Until now.

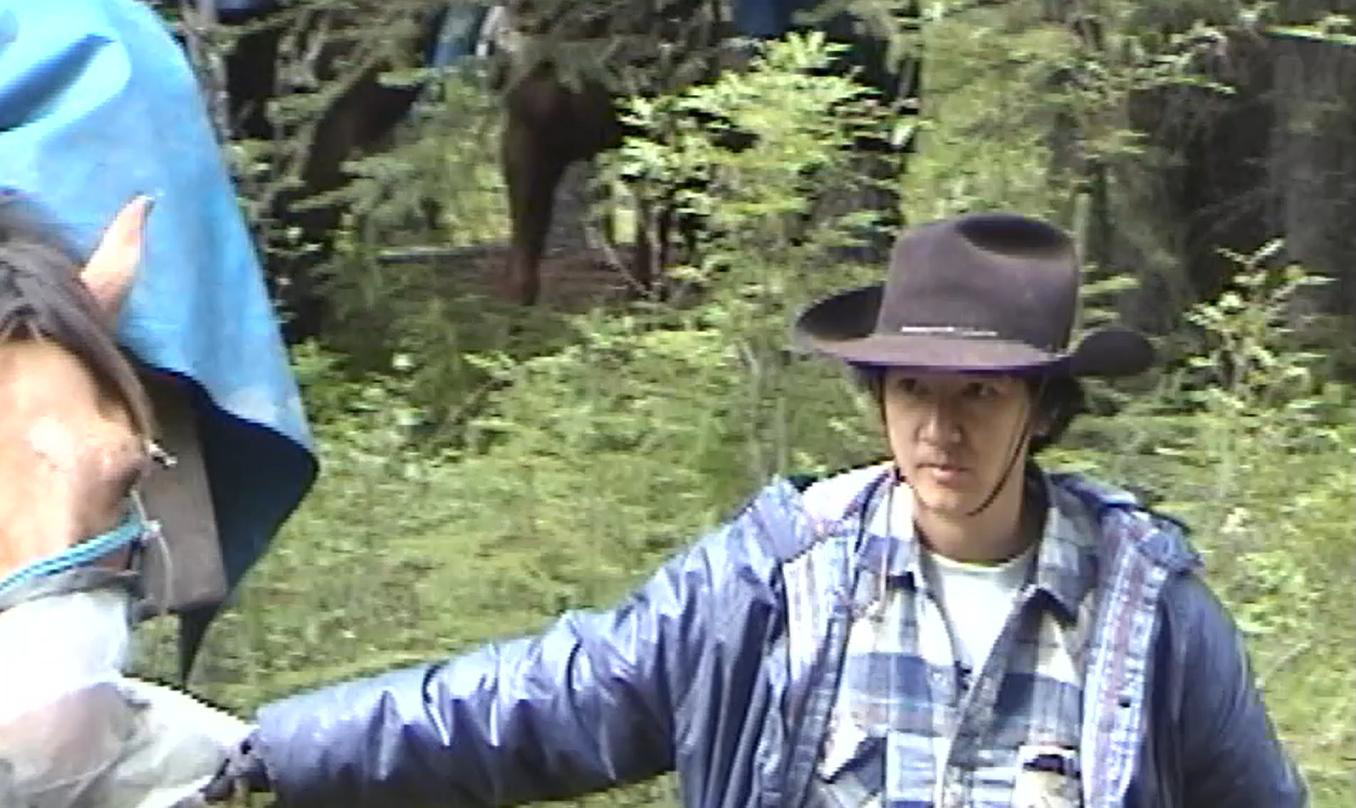

These images are taken from video footage of the trip up the Halfway River; The pack outfit trailing in; The kids being kids up remote Caribou Creek; Marlene tying up a horse after a long day; And Stan above camp scouting for a moose or an elk.