MANY FACES

MANY FACES

I guess that riding across a pasture, down a lane way, or along a road could be called trail riding. And I suppose that it is a good thing that we have those options since we cannot instantly wish ourselves onto the wilderness trail of our choice. But interesting trails spoil us. Plodding along a road just becomes mashed potatoes when, by comparison, trails with views, challenges, and unknowns, offer up a smorgasbord of possibilities.

Some trails change their look so quick and so often that we feel like explorers. Riding sharp and keeping our wits comes naturally, and a good thing since staying alert is not an option with changing trails and conditions, but about safety and survival. Great trails challenge us, make us feel alive, and we get hooked; a timeless bond with these trails of many faces that early explorers must have known.

One trail made me stand up and take notice. It had been a long day and reflecting upon the day made it clear that of the hundreds of trails that I had travelled, this trail had shown more faces than any other.

It had taken four hours to reach the alpine, steadily winding upward through spruce and fir forest. The trail was steep, any steeper and it would have been near impossible. But the trail was well cut and firm, only a few muddy spots and some small washouts along flat stretches of braided stream. Once we reached alpine the trail cut left and made a straight shot, gently, up a beautiful three-mile-long open valley. A few spruces scattered themselves pleasantly along the way and a few washes etched down from mountain peaks that marched alongside us. A pretty ride, well worth the climb, and we were rubber necked taking it all in.

At the head end we climbed a hump and found ourselves in the midst of looming peaks, scree slopes, and a few miles distant, an impenetrable chain of mountain craigs that held the river that we would make our way toward, then ride up.

But first, lunch, a simple affair, and joyful, everyone nearly ecstatic with the once in a lifetime panorama. In time, I knew, I may remember the view, but more so I would remember the camaraderie. Good people are trail riders who eagerly hit the back trails. Entrepreneurs would ‘can’ the rewards of wilderness trail riding if they could - a test of endurance, character, a bonding experience for employees, good for company production. Package it and sell it. The only production we needed to think about was getting down a steep loose shale slope and some rugged looking draws, one of which would lead us to the small river.

First there was a fifty-meter-wide bowl to ride across and then down, steeply, too steep to ride, and I watched to see who would mount up and who would simply walk to the slope and walk down. It is a sign of character, and common sense, who walks and who is inexperienced, too lazy, too rash, or too insensitive, to lead a horse down a steep slope. It is harder on a horse to ride down a steep slope than it is to ride. Everyone walked.

The shale scree was loose and the horse’s half walked and half slid down, sometimes threatening to smash into the riders. Everyone had the good sense to walk out at the end of the eleven-foot lead ropes. Jill’s sorrel gelding was a pushy sorrel gelding, a Haflinger gelding who had spent his early years successfully abusing riders in farm country. Riding the big trail had settled him down but he still pushed riders when he could. He is a good horse, just not yet an honest one, and Jill knew it. She walked out leaving a foot or two tail at the end of the lead, then snapped the gelding on the nose to remind him to respect her space. I admired her for taking control.

The trail dipped into thick alpine fir then dove down a ravine, following a small stream. At first the dirt trail behaved well but soon rocks began to appear. After half a kilometer or so rocks of all sizes from apples to watermelons with hard edges littered the trail. It’s times like this that you are glad that your horse is shod, never mind the ‘to shoe or not to shoe’ controversy. Your average trail horse’s foot would be chewed to remnants in a few hours. This is not a prediction, I have seen it time and again. Maybe you know your horse’s feet very well and your Percheron/Morgan cross has one half inch thick hoof walls that wear like iron, and so you feel you do not really need shoes. Maybe the big bone that your horse carries give you less cause to worry about sprains, pulled tendons, and stone bruises as well. But on this ride of hour after hour of rocky ground and sharp shale, over the days and the weeks, it’s foolish to take the chance.

And then Charlie, the raw-boned Percheron/Fjord cross gelding who at times wears no back shoes but has feet like iron, is constantly weaving on and off the trail, trying to avoid stones – a bad habit he picked up because at home he often does not wear shoes. He is a nuisance, rubbing and banging his pack against trees, then turning off into the forest to take his own, softer route.

Well, he is not carrying my sleeping bag. I hope he not carrying the lantern or the sat phone either.

Have you ever watched a horse step over stones? Let’s say you have a trail littered with stones, and a baseball size stone comes along. The horse plods along, sees the stone (not that he looks at it, there are hundreds of stones), and steps nicely over the stone. Makes sense. But then watch the back foot. The back foot of a horse does not normally step right in the imprint of the front foot, but just behind. Now, this back foot would normally belong exactly where the rock is, but, like magic, the back foot moves just to the left, or right, or back somewhat, to miss the stone. It's like a small miracle because there are hundreds of stones and it has to somehow remember exactly where that stone was, a stone that it did not consciously seem to notice in the first place - that it has already stepped over and cannot see any more!

Now the trail dropped hard, squeezed between the steep forested slope and the rushing mountain stream. The trail dips up and down, up and down, and weaves in and out, in and out, and large tree roots create steps that the horses have to jump down or up, jarring themselves under their loads. It’s these tough trails that weave in and out and up and down that will give a horse saddle rubs or cinch sores if they are inclined to do so. You can ride twenty level miles up a valley and be easier on your horse’s back than five miles of hard snaky trails.

Doghouse sized boulders on the trail now created dangerous cracks and holes. It’s time to get off and walk. It’s just as well. A downfall tree that cannot be ridden around blocks the trail. Jim grabs the trail axe and ties into the log. Chips fly, he seems to be enjoying the work. It’s good to get physical. Without a word said, Peter and Al get off their horses, walk to the front and insist on taking a turn. Good people these trail riders.

So we are in good shape, we think, walking down the last of the forest trail. The river is close, only a few hundred meters ahead at best. We can all hear its murmur as it slides through the valley. Marlene sighs with relief then remounts. I stay on foot because I don’t trust the valley floor. It’s getting softer. Mud now.

In fifty meters, the mud is boot top deep but still has a bottom. Then the mud reaches into the flat like black fingers grabbing at big willow roots and there is no good way to go. A particularly soft hole that holds mud and water traps us. My horse moves bravely along. I get off to the side so that my lunging horse does not jump on me. I can’t see what is happening behind me because tall willows block my view, and I can’t stop now. The chain is in motion. I think, ‘how many times have I gone through scrapes with my fingers crossed, praying that the riders behind do not meet disaster.’ I can’t count that high. I hear horses lunging, excited voices. Loud voices don’t help, even if you fall off a cliff. What happened already happened so it’s too late anyhow so keep your mouth shut and keep the horses as calm as you can.

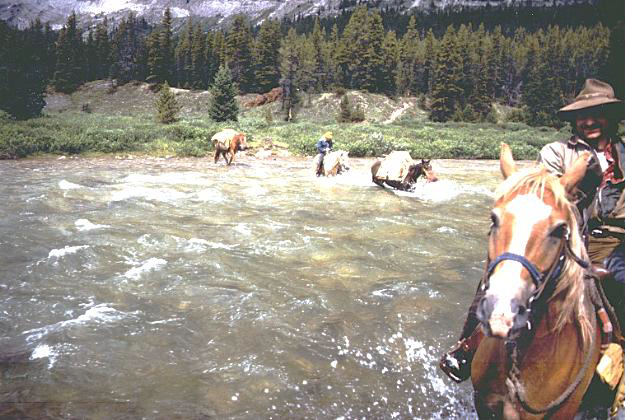

Somehow, everyone emerges along the riverbank. We breathe a sigh of relief, then a sigh of disappointment nearly in the same breath. We are of the same mind. We have been almost desperately looking forward to a crystal clear, friendly, mountain reiver. The one we now must cross. We want to bathe, drink pure mountain water, dip our trout rods and eat trout supper. The river is gross. Dirty, you cannot even see a stick a few inches below, and there certainly must be some in this dirty river, a river flooded from summer glacier melt. It’s unexpected, we all feel the same, there is not much to say. I am looking up the valley thinking worse thoughts. This river is no munchkin. It’s deep and fifty meters across.

Don’t mess with bad water. Water crossing have killed many, not as many as head or internal injuries from falls and kicks, but many. I know the stories. And I have swum rivers with horses more than thirty times (see the CORDILLERA! Expedition at www.vistapublishing.net). The memories flood back. Times that my life has hung by a thread, or has been held by a few inches of sand, send a deep chill through me. Some memories just seem to own you. It’s not just this crossing because there is no trail on this side, I just looked. It’s the many crossings that I am afraid of as we head upriver. We can’t even see the bottom, how deep the water is. Just one bad hole, one slip, one horse that panics….

But our group has common sense, and they read the river well, choosing to cross above the top of a shallow rifle, angling slowly down on to the shallow stones of the riffle. And the river bottom is firm and sandy with small stones. A big relief.

The outfit heads upriver and the trail is not much of a trail at all. Past riders seemed to simply ride the sandy river bars upstream, sometimes a hint of a trail through willow or grassy edges. The river valley is stunning, a half a kilometer wide grass flat then evergreens that slope upward to mountain shoulders and peaks. But I know what is coming. River flats between mountain slopes are schizophrenic, they just can’t keep a personality, hard ground one minute then fen bog the next. The soft ground comes, and we hold up. “What do you think?” Chad says, “Maybe there is a better trail in the trees along the mountain.”

“Go look.” Some smart aleck says. Chad does. Everyone gets off and makes small talk, waiting for his return. I look at the faces and I know each face hides separate thoughts. Some know that they are in no mans land and feel deeply uncomfortable without a trail to guide them. Others carry a wild streak, more reckless, and in almost a sadistic way want the challenge, no matter what happens. That’s my kind of trail rider. Riders that were born with wild hair up their butt.

Chad returns. No trail. We continue. As with many soft valleys the only firm ground is right along the edge of the river. Now, literally, only a foot width of firmness, maybe not even that. The horses struggle, at times lunging through fen bog. I am waiting and I do not have long to wait.

The stream edge trail, if it is a trail, is right next to the bank and it is literally inches to the water that is just below the level of the bank. But now we are riding along cut banks, and the water is deep. I do not know how deep. This is where you need to trust your trail horse and own one that is sure footed. No foolish jostling for position now. And my horse listens to me as I cue him away from sections of soft bank that look like they may crumble. But the other horses?

Again and again, we ride dangerously close on deep water banks. I am truly grateful for my sturdy, calm, Fjord/Percheron/Morgan crosses. And then everyone yells. I don’t see what happens. Bad stuff happens in milliseconds. Jill is in the water. She crashed off the bank. The horse hits bottom, and Jill is still in the saddle, only her chest and the horse’s head above water. The horse is lunging ahead, water flying from its nostrils. Jill keeps her seat, she is a great rider, and the horse lunges into shallow water and onto a gravel bar. Everyone has forgotten to breathe. We’re of a single mind, thinking, “my God.” Then Jill, soaked to the skin, has a big grin on her face. One at a time we get over the shock. It’s over. We begin to smile, then laugh. I would say that she is damn lucky. It’s amazing, you know, how often trail riders get through a scrape to live and love and laugh another day. Just darn lucky. Good people.

Because we have been riding upstream the river carries less water. It is shallow now, cleaner, and no longer dangerous. We are relieved and stop for a snack and a peepee break. When we mount up again, we ride with confidence and maybe that is why no one noticed that there was really no trail. The valley becomes narrow, and we ride a kilometer on river rock. I feel sorry for the horses whose feet slip and twist and slide on the rock. When I feel for the horses this way I get a small sick feeling in the pit of my gut.

Now, worse, a foaming water fall approaches. We can hear it for some time, and we look for a trail up and around it. We get off and check. There is no trail. We know that we have missed it.

Somewhere, back, I think, back before the kilometer of river rock riding there must have been a trail that cut up into the forested mountain slope, up and over, reaching around the rugged falls. We rode back, searching carefully for the sign of a trail. Then, after a kilometer of rocky backtracking a dirty cut sneaks off the river bottom, up into a brushy slide. We found the trail.

The day has been long, and everyone is saddle weary, ready to call it a day. But this is not just an exceptional trail experience, it is a truly great one. The trail now slices through brush and grass up the mountain slide at an angle. Pretty alpine flowers of many colors tickled the horse’s feet. The trail then heads up valley though dwindling fir forest, to emerge in a stunning mountain bowl. Snow, glaciers, and rushing streams cascaded towards us from all angles.

Once we are tired of picture taking it dawns on us that we need a way out of here. The only way out appears to be a goat trail at the head end. The beginning of the goat trail is tough to find but when we find it, it does look like a horse trail, but not for the faint of heart.

Now, experienced trail horses will dig in and climb straight up, literally until they slide backwards, and these were those kinds of horses. The problem was the multiple hard switchbacks and the fact that the horses will need to rest, and when they do, horses on the vertical could do all sorts of crazy things, like quit and go back, lunge ahead, or go off to the side on even more dangerous ground. We decided to go up in small bunches, walking and taking our time; time to rest and time to get over the bad spots without stopping to long. It was a scramble, any worse and it would have been impossible, but we did it. Good stuff.

So, the day is ending. We rode through a mountain pass that is surreal. High, green, short grass, dips and swells, filled the pass. Moon rock dotted the surreal, mottled, pass. A truly appropriate ending to a fantastic trail ride. A truly great trail of many faces.

Winter is creeping up. Time to reminisce, I hope that you have some memories from the many faces of trails that you have ridden. Their memory will no doubt help to keep us warm during long winter nights. If not, it will give us something to look forward to for the coming season.

Happy Trails!

Below are some images that give an idea of the abrupt trail changes that nature can throw at us. What’s missing is horses pulling up steep grades and sliding down steep grades. Just about everyone experienced with trail riding in forest, prairie, and hill country, is understandably amazed at what solid mountain horses with good minds and do.