MAKING SHOES STICK

MAKING SHOES STICK

As each riding season winds down, I find myself reflecting on the ups and downs of the past season and make a short list of issues and concerns that need to be addressed. And each season the problem of horseshoes falling off prematurely ranks high on that list. Trail riders regularly days or several hours of use. We can put a man on the moon, but it appears that we can’t keep shoes on our trail horse’s feet.

This is a serious problem. A horse that heads out on a lengthy ride over variable terrain and loses a shoe in the first few hours or the first few days can be in serious trouble. Maybe you notice the missing shoe and maybe you do not. Maybe you have many rocky miles to ride just to get back to the trail head. The potential for injury and damage is compounded if your horse has a small, soft, thin-walled hoof.

You would think that in these modern times the act of placing shoes on a horse would be standard procedure – like putting new brake shoes on your Chevy pickup that come with a 60-day warranty.

Unfortunately, it is not that simple. There are countless variations between the condition of horse’s feet, the type of shoes and their intended use, and the abilities, experience, and techniques practiced by farriers.

Through the years we have come to understand that keeping shoes on our horses is paramount if we are going to have a successful season. Barefoot riding is perfectly acceptable on many trails provided the horses’ hoofs are adequate, but for regular use on trails with rocky terrain shoes are a must. You need to spend a full day riding 20 miles up rock streams over stone and sharp scree, with heavy loads before spouting how bare feet can take all trail conditions. Over the years I have observed and consulted with many farriers. The information in this article is based on experience and discussions with farriers and farriers who assist other farriers, and who understand the needs of trail horses.

Contemporary farriers learn valuable theory to support their shoeing methods, but many farriers, both educated and self-taught, put shoes on trail horses that do not stay on as long as they could or should.

Many excellent farriers know how to put on shoes that stay on. Many others truly believe that their shoes stay on, and say so, yet habitually leave shoes vulnerable. We have been in situations when we have had twenty horses shod and within three weeks twenty shoes were lost or about to be lost!

Many trail horses are used long and hard. If your horse is ridden along roadsides, fields, and clear trails, the suggestions below may not be as critical as when horses are ridden over rocky, mud sucking, root filled, or brushy trails.

You need to check for loose shoes regularly and listen for a different sounding shoe as it strikes rock. A loose shoe has a higher pitch “clink” to it. Use the edge of your file above the clinch and hammer loose nails tight.

On a typical year I will shoe about twenty horses and about half of those a second time around. At times when I need to hire a farrier, I ask them to pay close attention to these details.

1. Place nails in all eight holes. Some farriers leave out the rear nails to allow the back quarter of the hoof wall to flex outward with the pressure of each step, rather than being solidly bound to the shoe. However, many horseshoes, like the St. Croix eventers, have the nail holes further forward than traditional shoes and there is really no reason to leave the rear nail out. When given a choice with traditional shoes like the toe and heel Diamonds, the rear nail should still be placed in as the rear nail is important in anchoring the shoe. The potential for injury after losing a shoe is far greater than the possibility of a problem developing from placing in the rear nail, which has been common practice for many years.

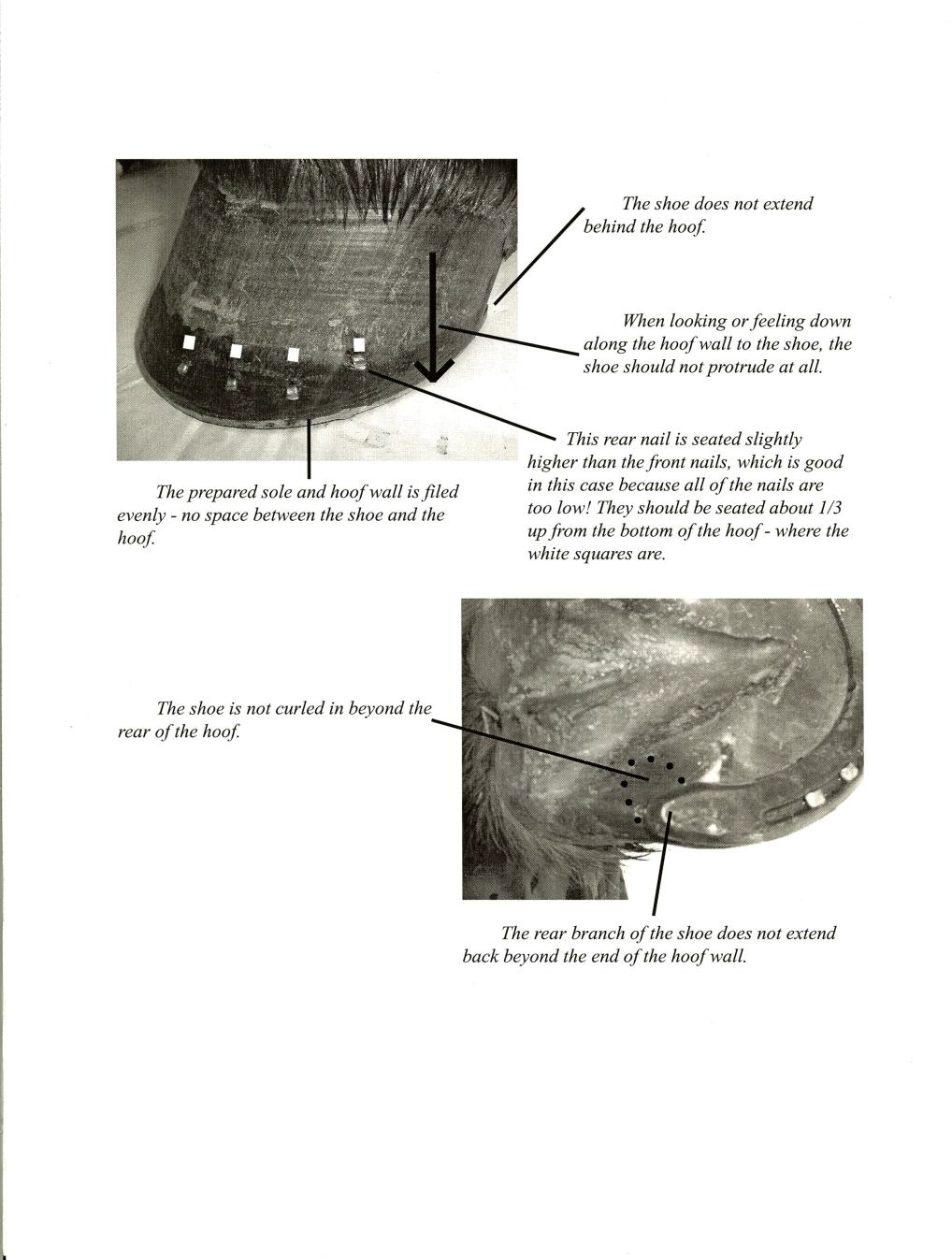

2. Do not allow the rear branch of a shoe to extend behind the hoof. Even if the branch of the shoe extends behind the hoof an eighth of an inch or less, every time the horse lifts its foot it has the potential to rub and catch on debris, eventually loosening the shoe. The reason some farriers leave excess shoe sticking out the back is to increase the surface area. I do not know how much of a benefit one eighth of an inch would provide but leaving it stick out is possibly the primary reason shoes come off while riding rough trails, or, having the rear foot catch on the protrusion when it steps forward. Many farriers will say they will leave only the width of a dime sticking out but in reality, it becomes the width of three nickels. Too much.

3. Do not excessively curl in the rear branch of the shoe. The rear branches of shoes do need to be bent inward to match the contour of the hoof, but excessively curling in the rear of a branch will leave it hanging to the inside beyond the hoof wall and when the horse steps on odd objects pressure on the curl will twist the shoe and eventually loosen nails. The curl can also catch on roots, stones, and other debris.

4. When the shoe is in place, and you run your hand down the hoof you should not feel or see the shoe extending beyond the periphery of the hoof wall. It needs to be seated flush or just inside the outer edge of the hoof wall otherwise each time the foot is lifted the shoe will rub and catch on debris, sucking mud, etc. Farriers will often place a shoe so that the rear half of each branch of each shoe is slightly wider than the hoof wall. This is so that when the rear quarters of the hoof flex out with each step they spread out to meet the full surface of the shoe. Again, it is good theory but if the shoe is wider than the hoof the shoe is more likely to loosen than if it is flush, under variable trail conditions.

5. The prepared surface of the horse’s foot must be flat, perfectly flush with the attached shoe. Any gaps (scoops) between the shoe and the wall will allow the shoe to flex with each step, eventually loosening nails and the shoe.

6. The nails need to be placed so that they come out in a pattern an inch or slightly more from the bottom of the hoof. Too often nails emerge shallow, a half an inch up or less, allowing nails to pull through, especially on thin hoofed walls.

7. When the nails are finished being clinched (bent over), they are commonly rasped flat to reduce bulk. Lightly rasping them is fine but excessive rasping will result in the remaining bent nail breaking off when riding through rocks and roots. When the clinch is gone nails tend to loosen and pull out much easier.

8. The angle of your shod hoof in comparison with the ground will affect how soon the foot breaks over, and so, how long it stays on the ground. The longer it stays on the ground the more chance the shoe has of being “clipped” by the rear foot and the more likely it is to loosen and come off. Farriers generally understand proper angles and par, rasp, and trim accordingly.

The farrier who shod a horse that is happily riding over prairie trails may earn kudos from a satisfied horse owner, but that same horse owner might howl with anguish as the same shoeing job hits the big mountains and shoes fly off after a day or two of rocks, roots, and mud. If you have an open-minded farrier, you might ask him or her how they shoe trail horses. If they get offended there may be a reason for it or they may not need your business anyway, which is common with good farriers. It is often tough enough to get any farrier to show up at all, and so horse owners are reluctant to ask questions for fear that it may be taken as an insult, questioning the farrier’s ability or way of doing things. Likely, the friendliest way to get an understanding of how trail horses are shod is to ask a few questions on the phone when you book your appointment, and some form of a warranty is not out of line. If a shoe comes of in less than a few weeks do not blame the terrain. Many ranchers, outfitters, and trail riders ride shod horses for weeks on end over all terrain without losing shoes. It’s more about common sense than rocket science. How much common sense did you learn from going to school? Aside from the school of hard knocks, which could have happened at school!

Happy Trails!

What some farriers learn in school does not always agree with how other farriers shoe for trail riders and outfitters. For example, some learn to not put in the last nail at all, so the rear of the hoof can flex outward as would happen naturally. But for us and many others, the last nail is the most important, what keeps the shoe from loosening over weeks of tough trail use. It is often seated deeper that the front 3 nails. The serious injury that can happen to a bare foot that was recently trimmed, when a shoe is thrown, vastly outweighs the theory of allowing a greater degree of flex in the hoof.

Trail horses working under load need to be shod for most mountain trips. Riding many miles daily on rock and scree for many miles would destroy many hoofs in less than a day. This is compounded with thin-walled hoofs and soft walled hooves, or both. I have seen a horse with a soft white hoof wall lose a shoe that no one noticed, and in 3 hours was limping badly and had to be retired from the ride needing a month to recover. Other horses, for example ‘Speck’ from the Cordillera Expedition, went close to 1000 miles with no shoes, having lost them in the first few days. But Speck had days of forest walking with little or no stone to balance off the river rock or alpine days.

For longer difficult trips, taking shoe boots as emergency shoes that will fit most of the front feet of your horses is a great idea.

Shoes that may last for a month while riding fields and forest and round pens, could be tossed in a few days when riding long days on tough trails of rock and roots and mud.