IT’S A MATTER OF HEART

IT’S A MATTER OF HEART

From where I sit, I can look out the window and see more than twenty trail horses, and I can look across the table and see a hockey photo of my son, who is streaking down the ice at Vancouver’s ‘Challenge Cup’. I think that horses and hockey players have something in common, something that everyone wants to see in a trail horse or a hockey player - something called ‘heart’.

If you are a trail rider or a hockey parent you have likely heard someone, say, “Wow, does that kid/horse have heart!” But saying it is one thing and understanding it is another. If you have been riding in the hills or the mountains for a few years you may have experienced the difference between an average horse powering

its way up a hill and a horse with exceptional ‘heart’. And what a huge difference it can be, like pulling a two-horse trailer up the Coquihalla Highway with a VW bug compared to a one-ton Cummings diesel.

Experiencing the difference is unforgettable but understanding where heart comes from and how to harness it may be as clear as the mud churned up by that horse with heart. It is illusive. If ‘heart’ was easy to capture, we would bottle it and sell it for millions. If we could mix it with truth syrup and convince politicians, bankers and oil executives to drink it, we could all live in a brave new world. Here are some thoughts and stories about a horse’s ‘heart’.

First, do not confuse ‘heart’ with nervous energy. People often convince themselves that their horse shows heart when, in fact, the horse shows misguided energy. This energy may be a display from a lack of respect for the rider, a lack of training, improper training, fear, programming for competitive events like racing or roping, or genetically hot bloodlines. Experience has shown us that high energy and nervous horses lack bottom and will actually quit or slow down or even quit when several tough hours are on them and you look to push through some tough terrain or up some steep country. These horses can also be dangerous.

Several years back, in the Mackenzie Mountains of the N.W.T., a wrangler commented on how much heart his horse had. The horse was constantly moving about and seemed wound up like a tight spring. My impression was that the horse lacked respect and had an excess amount of nervous energy. Several days later the cowboy dallied his lariat around his saddle horn and attempted to drag a log into camp for firewood. The horse freaked at the sight of the moving object. It went into a bucking frenzy, caught the cowboy in the rope, dumped him and pounded him a little more. He survived but was beaten up badly, and now I wonder if he still defends his horse as a good horse with lots of heart.

Some horses eat up work like candy. They can be obsessed with work ethics. I have seen horses, when, if not checked or rested, will continue climbing a steep slope until they nearly drop with exhaustion. This type of willingness is more bred into the horse than it is trained into the horse. It is a genetic gift, the attitude we often associate with workhorses at a pulling contest. This genetic gift is not far removed from an Arabian that willingly runs all day or a Thoroughbred racehorse that lives to sprint around a track.

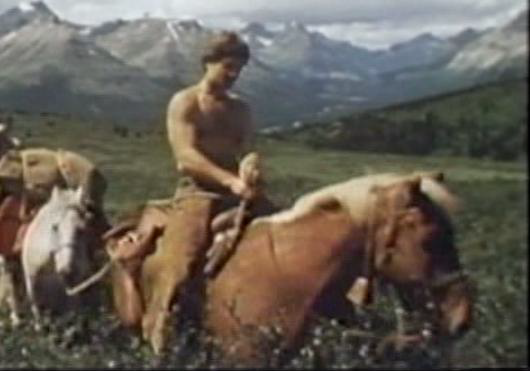

Last fall I was headed out of the wild country at the end of a trip. I was riding Sunny, a solid 15.1 Fjord cross with as much heart as any horse I had ever ridden. We had begun to climb a steep two mile pull from a river bottom to an alpine pass. At this point in the season Sunny was in great shape and I gave him his head, letting him decide when to stop and rest. Well, I knew he was a working fool, but he just did not seem to know the meaning of quit. How exhausted he was did not even seem to fit into the equation. I had to hold him in check to give him a rest, he would have driven himself to his knees, it seemed. It’s impossible not to admire a horse with that much bottom. It makes good sense that many breeders of trail horses like to see some ‘cold’ or ‘draft’ blood, the working breeds, in their trail horses. Aside from generally providing some bottom or work ethic they can also provide a calm nature and bigger, stronger bone and foot.

Another example of inherited work ethic was a three-year-old Morgan/Percheron that we had on his first horse camping trip in the Yukon. We had a few tough days in and at the end of the day. We were ready for a rest, but we needed to cross a small but deep and bottomless creek that wound its way into a pretty mountain lake. Crossing the stream would have been a disaster. The lake bottom appeared more solid, so I led the outfit along the lake shore and began to cross where the creek dumped in. Everything was fine until the exact point where the creek came in, when the water dipped to the depth of a person’s neck and the bottom turned to muck.

Horses panicked, splashed, flopped about, and turned and struggled back toward the solid shoreline, all except one pack horse, a dark mare that was seriously mired. Back on shore I removed a couple of forty-five-foot lash ropes, tied one end to the mired horse and the other to the empty packsaddle of the young morgan. I pointed the young horse into the brush, said “Hiya!”, tapped it on the butt, and watched in amazement as the horse leaned into its chest collar, found its footing, and continued to pull, skimming the now unstuck horse across the water like a fast fat duck. What was truly impressive is that the horse continued to drive straight into the willow brush with no encouragement or guidance from me, for sixty feet, until the horse was safely on shore. This was not something that was taught to the horse, it was all about heart and instinct.

My new saddle horse was a sixteen-hand wall eyed paint that looked like it should have been a good trail horse. But I was suspicious. Earlier, when the horse was brought into the herd, it had shown cocky and arrogant behavior. It is not uncommon for horses to bicker and fight to find their position in a new herd, but this horse appeared to carry this disposition as a fixture. He was, or thought he was, the ruler of the roost, nipping, biting, and pushing himself upon other better-natured horses. I had thought, perhaps, that this dominant behavior would translate into a trail horse with determination and drive.

As the days and the weeks on the trail progressed and the horse realized that he had to submit to the rider as the dominant being, and working as a way of life, he began to sulk and became difficult. Rather than accept trail conditions willingly he would hesitate and fuss when asked to navigate trail obstacles. Over the season his aggravated behavior resulted in a loss of body weight. The lesson here is that because a horse is aggressive or dominant it does not necessarily follow that it has ‘heart’.

I believe that when we refer to a trail horse’s ‘heart’ we are speaking about its willingness to work, endurance, power, and steady disposition, all qualities that trail riders should appreciate and look for when buying or breeding trail horses. These qualities are not necessarily more important than respect, friendliness, or softness (responding to cues willingly), but they need to be considered.

There are other factors that may affect a horse’s drive and endurance including the horses health and age. Horses need good nutrition if they are expected to have vigor. Worm infested horses will often be more lethargic which will affect the horse’s willingness.

Just remember, some horses are like some men or women, they look good from far, but they’re far from good. If you go through life having known a good man or woman and a good dog, then you are lucky. If you have known a good man or woman, a good dog, and horse with ‘heart’, then you are lucky indeed. At this moment I am looking out the window at our horses. I see more than a dozen horses that have, through the years, risen to the challenges of countless hills, rivers, tangled forests, bogs, and long days, and have done so faithfully. I am fortunate indeed.

Reading and editing this article was an emotional experience. At one point I had to quit and gather my emotions. These horses had taken me over thousands of wilderness miles, countless mountain passes, endless steep grades, hundreds of river crossings, saved my bacon again and again. Who I saddled, wrangled, fed, caressed, the days for my life for 50 years. They will always be my family. These horses truly had it all, and above that, they literally would push and drive forward, over any terrain, up any mountain until they dropped, if I asked them. They were born heroes. Hearts as big as the mountains they climbed, and honest as the month is long. All these horses lived to old age.

So, for me, this article, these horses below, and more, is a tribute to those horses that are the epitome of what I write and speak. I love you so much:

Lucky. A big boned quarter horse for a big man who competed in calf roping. Lucky used his endless will to drive forward – over one thousand wilderness miles, 27 river crossings, endless bog and bottomless backwaters, he led the way for the outfit, made the Cordillera! Expedition a reality. Lucky was a good name, and a great horse.

Lucky is the horse that I most rode for over 20 years. His stamina was endless, super powerful, never hesitated in tough going, a wonderful ‘personality’. A man-sized horse kids could ride.

Brass had two names, Brass, and Baron. He was a direct descendant of Justin Morgan, the founding horse of the breed. Pure, big, strong, old time Morgan. He had everything, including great looks. He was not a people lover but was honest to a ‘T’. Did everything asked to perfection and great on his feet over rough ground. Never shirked a task. Took every command as gospel.

Donny is the first-born Morgan on our property. He defies logic. Pure morgan, could have been a show horse, son of Windhover Regency, the

most used Morgan Stallion in Canadian history. And yet bone and hoofs like titanium. Heart of a Lion, but an absolute sweetheart that kids loved. A lead horse by heart and all other horses knew it. He just had to be up front and took that role seriously.

The most trips of any horse ever?

From two years old until now, 33 years later. 29 of those years on trips with Blue Creek. Count the pack trips – each pack trip from 2 days to two months long; 4 with the clinics, 3 summer trips, 4 fall hunting trips x 29 years = 319 trips! And never one single issue. We all love you, Donny! But I love you the most.