HORSE CAMPING PART III

HORSE CAMPING PART III

Spring is here and so is a new beginning for horse riders. Days are longer, the weather more pleasant, and we put into action those horse activities that we have envisioned, planned, and prepared for during this long winter season. The cycle of horse-related challenges, successes and failures, begins, again. And horse riders are good at going back to the drawing board. Both seasoned and novice riders learn early in the game that horse related plans rarely unfold as expected. We face challenges.

Where and how we keep, board, and ride horses is in constant flux. Our horses themselves can change with physical problems or unexpected behavior. And economics can change. The cost of participating in our desired field of performance can be debilitating. Time and again I have witnessed frustrated horse owners and riders set to walk away from the dream that was not the reality.

Enter trail riding. Really, what is our connection with horses? It’s spring! Rediscover the feel of the horse, its power and its ability to go places, special places, wild places. It’s all about losing stress not adding stress. And it’s about contentment, happiness, and appreciation, appreciating the good company of trail riding and camping companions and appreciating the beauty and detail of the great outdoors. Rediscover your horse and yourself through trail riding and horse camping.

This is the last of three articles about horse camping. Let’s have a look at being on the trail; trail tips, wrangling, and camping.

So, you’re ready to go! You have taken care of business, and you are about to leave your cell phone and civilization behind. You have calm, friendly horses, you are packed simple, and light and your hitches are tight. You have checked the rigging on your riding saddle, your axe and saddle bags are secure, and you carry some essentials on your horse like a warm coat and rain gear rolled up behind your cantle. In your saddle bags will likely be some food, drink, camera, binoculars, extra gloves and hat, fire starter and matches; not too much weight or bulk. S high cantle pack is dangerous when you need to get on or off quickly – and at times you will. Be sure that there are no loosely tied objects on your saddle like jackets. These items can spook a horse, especially upon leaving.

Coordinate the leaving. Someone needs to take control. Be sure that everyone is ready to go before anyone mounts up. Be sure that there will be no immediate delays like looking for misplaced gloves or needing to relieve oneself. You should have looked for the trail head before mounting up to know exactly where you ride into the woods. Avoid having unnecessary objects hanging from you or things in your hands(food). If you are taking a small day pack be sure that it is light and not too large. I prefer to hang mine on the saddle horn on the offside.

If you are leading a horse the lead rope should be ten to twelve feet long and your saddle horse completely post broke meaning it stands still when you mount and when you get off to perform chores or to get out of tight spots. Having your saddle horse turn circles as you hold the lead rope of another horse is dangerous. If the rope gets under your horse’s tail you could go for a buck. Do not worry too much about who is up front, but it is a good idea to have calm and dominant horses ahead as well as someone who is capable and who knows the trail.

Never tie the lead rope of the horse you are leading to your saddle horn, simply hold it, or one half a dally, and avoid having a fixed loop at the end of the lead, as the tendency will be to loop it over your saddle horn. Things happen on the trail and if you need to get off in a hurry, or get dumped off in a hurry, you do not want to get caught up between horses and a fixed lead rope.

For large trail groups with several packhorses, outfitters will often prefer to keep riders and packhorses in separate groups, some distance apart, but with a few riders and a few pack horses, the riders should stay within communication range. The lead rider and the last rider need to be able to talk about unexpected stops, trail conditions, slipped packs, and who knows what. The rear rider generally has the job of pushing ahead to keep the outfit tight. The lead rider can slow down but then the outfit loses distance, which is fine if you are not in a hurry.

Generally, you are better off leading packhorses than allowing them to follow loose. The more horses loose, the more trouble. However, in difficult terrain, thick forest, and uncertain trails, horses led in tandem will get wrapped around trees and brush, so we often lead a few individually and let a few reliable horses trail loose. If a horse is tied to the horse you are leading, it should be tied with a breakaway string to the packsaddle. Tying directly to the pack saddle with a lead rope or tail tying prevents horses from being able to break loose. If you get in a bind you want the horses to break apart rather than be wrapped up in a chaotic wreck. Bailer twine is about the strength of break away string that we use.

As you are riding along as part of a group always be a pro-active rider. This means that although all the horses are turning or stopping, and yours will too, you need to signal those cues to your horse at the moment just before the event. Then, and only then, are you in control of the horse’s mind, which is important if you expect control later when you want to take the horse away from the herd and go for a ride.

Never say ‘whoa’ unless you know that you are going to stop. If you say ‘whoa, whoa, whoa’ when you slow down only, then how does the horse know to stop dead the next time you say it? Say ‘easy, easy, easy ’ to slow down and ‘Whoa” to stop.

When your group stops for a break, everyone needs to lend a hand. Do not let one person catch loose pack horses as you enjoy the scenery, and do not expect loose pack horses to hang around as you enjoy the scenery. You will cause yourself mountains of grief if you leave horses loose, they always need to be under control while in the wilderness. Having said that, for short stops with a couple of loose, tired, and reliable horses we will often just watch them carefully until we leave. When you get to camp always unpack the pack horses before unsaddling the riding horses as they are under load and the empty saddle horses are not.

Tie horses short to a tree or solid object at nose or eye level. Short means 1 to 1.5 feet from the horse’s nose to the tree. Do not allow them to feed unless on a proper picket line or hobbled. You may think you are being kind by giving them more than two and more feet of lead rope when you tie them up but you are being mean. You are making them think they are loose when they are not, and you are creating unnecessary movement, getting all the horses stirred up and risking getting a leg over the lead and a pulling frenzy.

When you stop for a break be sure that you place your reins over the saddle horn. Better yet, give them a few twists first or tie them with a saddle string. Horses are good at shaking off reins, stepping on them, breaking the reins and hurting their mouth. Leaving reins sit on the neck is possibly the most common ill deed that novices repeat. It is a sad moment when you just leave on a trip and your reins are in pieces.

For those moments when your horse is standing on something it should not be, like the lead rope, take your foot and firmly slide it down the horse’s leg, from the knee to the hock. It will quickly lift its foot.

Be sure that you match your ability with the difficulty of the trail. Do not head into difficult wilderness with few trails until you have many miles under your belt. And do not force yourself into long days to get to where you need to be. Four to eight hours a day is enough, particularly early in the season when horses are soft. Sure, we have put on many long ten-hour days in the past, but we save that for late in the season, and usually for the last day coming out. If you are going to earn a gall, cinch or wither sore, that is often when it will happen. Sores can also happen from packs rolling on fat, soft horses. If you can, ride a soft out of shape horse until it slims down and toughens up somewhat, before you pack it.

Brush your horse daily as a habit, checking for rubs, bug bites and scunge build up, especially in the girth area. Bugs in the woods can chew up your horse and create open sore areas. A good quality bug dope is a must for trips when bugs are out. We carry a medical kit with bug dope, wound salve and spray, bandages, and, on longer trips, penicillin.

Wrangling is simply caring for and managing horses while on the trail. It means making sure horses do not get lost, seeing that they get good feed and water at regular intervals, and managing their movement to and from camp. Good wrangling begins by choosing a good campsite. This means an area with good feed so that the horses do not have to leave the area to search for feed. People often wonder why their horses took off when often they were just looking for better food, although some horses do not need a reason for taking off.

Be sure that water is accessible. There needs to be access to that stream, lake, or pond. Also, if it is raining or the grass is wet, horses will not need standing water. It is interesting to see horses prefer to drink from a mud puddle when a clear stream is a few steps away. It just goes to show you that you can lead a horse to water, but you can’t make him drink the clean stuff.

We have camped in some very ugly places with poor feed, but only for a night. So, if you need to stop for one night in an area with poor feed you may get by with limited grazing, but it is not good for you or the horse to have them work hard all day then scavenge for slim feed.

Make your camp between where the horses are grazing and the trail you came in on as they will generally want to leave back the way they came, and you can hear them go past your tent at night. We have bells on all our horses. Many, many times I have heard the single ‘tink’ of a horse bell, walked through the woods or over the hill and there they were. Eight delinquents, yet only one ‘tink’ did I hear. Murphy’s law – it’s the horse that you did not put the bell on that would have made the ‘tink’ that you did not hear. And made you walk for many frustrating miles looking for nothing.

Horse stomachs are not particularly large, and they are designed for multiple, lengthy, feeding times during the day. It is not acceptable to ride a horse all day, let it feed for one hour, and tie it up for the night. We consider two hours morning and night the absolute minimum, and on my trips, horses are out to graze all night. If I am concerned about hobbled horses hopping off, I may choose to picket a horse or two, being sure they are on good grass and being watched so that they do not get tangled.

Horses on a picket line should be on a rope with a swivel to minimize tangles. The rope should be soft, three quarters of an inch or larger in diameter, and the rope should be attached to a foot rather than the halter. Most riders use the front foot, but we find the rear foot safer provided the horse is trained to accept the rope on its rear foot. Always walk the horse to the end of the picket line before turning it loose.

We believe that turning out horses with hobbles is the best for the horse and the best for the environment. Tying horses to trees for lengthy periods, high lines on soft ground, and picket lines, is more destructive to vegetation than free grazing. Horses should be broken to hobble before you leave home. Use a hobble that allows a medium shortened step, say eight to twelve inches between the collars, as opposed to a narrow standing hobble.

While in hobbles horses can make time and run faster than you can, so if you do not trust your horse, and I don’t, try using a sideline as well, which is a hobble from the front to the back foot, about thirty-six inches between feet. They need to be trained for sidelines, never just put them on the first time and leave them on their own. Some horses just cannot get along with sidelines and will rub their pasterns. The mountain people of Tibet use only a sidle line with no front hobble at all.

Most hobbles have a protective sleeve around each foot, but you will see many experienced outfitting horses with a chain link hobble also have the chain as the sleeve. If the horse is well broken and puts no pressure on the hobbles, the chain can be better as it does not hold moisture and is easy to work with in freezing weather. There are many hobble designs out there and most work well. We prefer to avoid wide strap leather models as they are often difficult when wet or frozen, and if wet for long periods will slip hair. When on the trail and removing hobbles, we always place them around the horse’s neck. They are on the neck or on the feet, if you lay them down you will lose them, and that can be a real issue of concern.

Finding, controlling, and leading horses back to camp is an art. Remember, no loose horses, wrangling means that horses are always controlled. Unless you are a seasoned wrangler and know your horses very well you should always tie your horses to trees or to each other before you remove hobbles and lead horses back to camp. If it is a shorter distance back to camp, say a few hundred yards or less, we will often tie a few of the dominant horse’s neck to neck, or tail tie them, and lead them in and let hobbled horse make their way back to camp as we head in. If needed, we return to get the hobbled horses. Do not lead two or more horses with separate lead ropes in your hands. You can easily get into a tangle, have leads stepped on, horses tangled, and have loose horses disappear.

There are some compact electric fencing systems that fit nicely into a pack box. We have used them at times, and they work for a few horses. Be sure that horses are trained to respect the hot wire at home before you leave and be sure horses hobble inside of the hot wire as they can, and do, break out at times.

Truly, wrangling is what separates future horse campers from the wanabee’s, but you can’t really blame the wanabee’s for being two legged quitters. Sometimes it feels like you spend more time saddling, packing, hobbling, finding, and leading back horses than you do actually riding. Sometimes you go for a five-mile walk to find horses and your day is half over before you get going. The bottom line is that you really have to like working with horses to put up with it. If you find you are tying up horses to trees overnight regularly, without proper highlines and feed and water, and having them feed only an hour or so morning and evening, then back country horse trips may not be for you.

Campsites are, to me, a source of amusement. You can give two groups of campers the same equipment and one camp will be an act of perfection: tents tall and square, gear in order – something to make one feel proud. And another camp a total wreck; the tent looking like a rag on the ground and the campsite like a bomb hit it.

Start off with a good site, particularly good access to wood and water and a flat spot for your tent. Take the time to flatten out bumps where you sleep. We commonly use the dull side of the axe blade to knock down bumps. Try to camp in an area with good trees to tie horses to. And if you leave horses tied to trees for more than a few minutes, put hobbles on. It keeps horses calm and keeps trees from being destroyed.

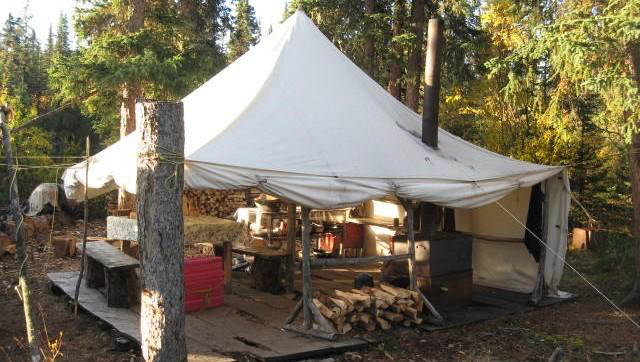

The tent that you choose should match the trip. If it is a summer trip and you are on the move then a light stand up dome tent, quick to set up, and a fly to cover your cooking area, may be in order. If you are a late season hunter with a main camp, then maybe you need a wall tent with a wood stove. There are many wonderful tent designs out there and it should not be difficult to find one that suits your needs and your budget. I avoid small backpacker type tents as the horse can handle the extra few pounds to give me the room to stand up in, and the room to have a lantern in and cook in if things get cold or wet. Evenings in a tent you can stand up in with a glowing mantle lantern are SO much more enjoyable than a backpacker tent.

There are many light synthetics out there and a canvas wall tent that weighs sixty pounds can be had in a synthetic at twenty pounds. The difference will make a horse smile. I do find canvas friendlier than synthetics in wet or cold weather, and synthetic tents often leak at the seam areas, even new ones. Treat them well with water repellants. We always use bedroll covers over our sleeping bags so we do not have to worry about a drip or two. In fact, here is a lesson to the worrisome; unless the water drips are getting your bag truly wet, in which case you should cover yourself with a tarp, then, don’t lose sleep over it. Tents are like people, rarely perfect. I have seen people worry themselves right out of enjoying a trip because a tent or gear did not act perfectly. And I have been on other trips, where everyone had a jolly time with nothing but a tarp for a tent, and a pot and matches for cook gear.

So, let’s look at our gear list. Always take warmer clothes and sleeping bag than you expect to need. Use quality rain gear. Many riders prefer the outback style rain gear, but you may find a good pant and jacket type better if you expect to do much walking. We use the tough waterproof gear bags and bedroll described in the previous articles. The bed roll keeps you warm and dry and your sleeping bag clean.

Our kitchen includes a light folding fire grill, a thin profile propane camp stove, a lantern, a cutlery pouch, a collapsible water bucket, and often, folding tabletops. Again, there are so many stove and lantern types that you can choose what suits your needs the best. Always know where your lantern is so that if you get into camp late you can unpack that horse first and get your light going.

For those late nights getting to camp and late-night forays out of your tent you will find a head lamp invaluable. If you have never used one, you will wonder how you got along without it. And same goes for a quality Leatherman type multi tool on your belt. There will be many times on your trip when you need to cut, grab, poke or screw something.

Along with your three-quarter length quality trail axe (loggers limbing axe) you should take a good camp saw. A camp saw is safer for cutting firewood and it can cut sizable trees across the trail. There are good trail saws available. We often use a compact, aggressive tooth, cut both ways, wood saw, readily available at the local hardware store. We keep the saw in our fire grill bag. Paint or tape your axe handle and axe scabbard orange or red as they are great at hiding in grass or brush.

Camping with horses does mean that we can enjoy the luxury of a few extras, like a portable shower (use biodegradable soaps), and big jars of peanut butter and jam. Just remember – light, trim, and tight. The less stuff you take the less time wasted packing and unpacking, the fewer horses needed, and the smoother your trips will be.

Each of the areas discussed; trail tips, wrangling, and camping, can fill a chapter themselves. One of the big differences between a recreational rider and a professional outfitter is that the outfitter has a long memory full of vital details. The pro knows how little things quickly become big problems and knows how to deal with these situations before they become problems. Pros have an endless mental library, a way of doing things that helps trips go smoothly.

Having said that, the beginning camper with calm horses, a good hands-on attitude, limited numbers of horses, good gear, secure hitches, and a good trail, can safely enjoy the great outdoors. In fact, you may become a horse camping addict. Just ask my friends and clients, Pierre and Christine, who take remote trips every year, and they are in their eighties! If you want to enjoy the experience but it is not practical to purchase or keep the extra horses for packing, or you lack the experience to get going, consider taking you first trip with an outfitter or use experienced outfitter horses that are available to private individuals. A trail riding/ packing clinic is also a great way to share knowledge and camping experience with like-minded individuals. Good luck with your horse camping adventures!

HAPPY TRAILS!

You are all ready to go, done your homework, great gear, everything tight and you are ready to mount up. Well, the horses are pumped too, keyed up, and that is often when things go wrong. Coordinate the leaving, who is leading what, who is out front, who is at back. Don’t anyone get on until all horses and riders are completely ready to mount – no garbage lying about, gone to the toilet, etc. Then, and only then, someone says, ok, everyone’s ready, mount up.

Always be a pro-active rider. Even though you are in the middle or the back, give your horse the cue just before the act happens, meaning in the second before the horse is about to stop, or about to turn – say whoa, or apply leg cues, etc. Then your horse will be in tune with you as alpha and be more willing to obey when you head off with the horse in the future. Don’t just be a sack of potatoes, someone stuck on a horse. After all, you didn’t just fall off the turnip truck yesterday, did you?

Keep a tight string as you ride. The lead rider needs to be aware about what is happening behind and not get too far ahead, but it is the last persons job to keep the string moving at the pace the lead rider sets, within reason, and they will need to push their horse forward at times to keep the string tight and everyone within communication distance.

It is your responsibility to pick a campsite with good grass and water, and to make sure that the horses get good feeding time. It’s the least you can do for all their work effort.

Whenever possible, place your tents at the area where the trail entered the grazing area. Back out the way they came is likely the way the horses will try to head out again, and likely when no one is watching, like 3 am, when you hear the bells cascade toward your tent. You really need to keep a head lamp and lead ropes close by, get up quick, get in front of the horses, and tie them up to a tree and put hobbles on then go back to sleep – done it a hundred times. Keeping hobbles on horses when tied to trees in camp keeps them from pawing, which keeps trees from being destroyed and also gets then to relax, instead of all worked up and getting each other worked up.

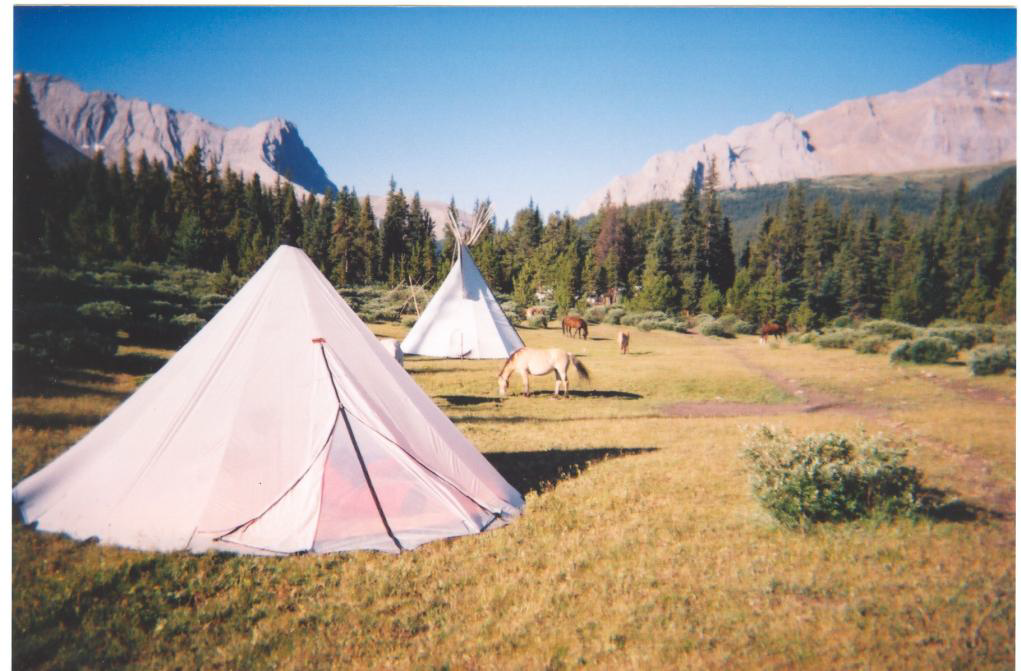

Really, who doesn’t love life in a wall tent – the natural smell of canvas, a wood stove to keep you pleasantly warm and dry in any weather, nice and bright, lots of room to cook and sleep – it’s the good life, as far as camping is concerned. Of course, weight and set up time is the issue. There are many good synthetic wall tents out there. A canvas roof and synthetic sides is a good compromise. The pyramid design shown is quicker to set up than rectangle. Having said that, our pack trip tents are most often a quality 3 or 4 season 8x8 to 10x10 foot dome tent. Fast to set up and take down. We hang a lantern in them to keep out the frost on cold nights and make things cozy in the evening. Bring in the pack boxes to cook and sit on if needed. One tent for 2-3 people.