FIRST AID FOR TRAIL AND HOME

FIRST AID FOR TRAIL AND HOME

Understanding first aid for horses is a work in progress, a lifelong learning experience born of necessity. Injury, illness and disease is not pleasant, but it is a reality for trail riders and horse owners who have kept and ridden horses through the years. The list of injuries, sickness and conditions that can and do occur is overwhelming, and the understanding of symptoms, treatment, remedies and medicine is more overwhelming. David Levine, DVM and Clinical Associate said it well, “if you take ten people you get ten different opinions on how to treat wounds…” While researching this topic the contradiction and opinions about recommended medicines, remedies and treatment was surprising and frustrating.

I am not a vet and do not pretend to be one, but years of hauling, remote riding, and keeping large numbers of horses, combined with a background in zoology, has provided some insight into the subject. There is no question that ranchers, outfitters, and trail riders need to understand and respond to injury, particularly first response. A vet should always be your first choice with any serious injury for several reasons including the fact that they have the experience and medication needed and the recommendations they would make for continued care and recovery. However, the reality is that a vet is not always accessible or available.

When we look at the injury and sickness that can and has occurred during our forty years of trail adventures from stone bruises and sprains, strained shoulders, cuts from branches, damage to the coronet, colic and sickness like equine anemia, a casual rider might be inclined to say, ‘why go out there if these things happen.’ However, the reality is that just as much, if not more, happens at home and with casual trail riding, from horses banging and cutting themselves while being loaded and hauled in trailers, wire cuts, cuts and pokes from sticks, kicking each other, getting cut and scraped on objects around the farm and who knows what. Horses are creative and invent ways to injure themselves you never imagined.

The depth of information in each area I will address is endless, colic for example, could be a two-part series itself, so for our purposes we need to focus on symptoms and what to do about it – first response and treatment.

Assessing an injury is mostly common sense. If it is a minor injury, then minimize movement by tying the horse up first and continue with treatment. If it is a more serious injury and the horse is very excited, moving around, in a confined space, or there is debris about like trees, brush, wire or other horses, keep your own safety in mind first. Do not place yourself in a dangerous situation by barging to manhandle a distressed horse. Blood is not pleasant to see but a horse has about 55 liters of it and can lose about twenty percent before beginning symptoms of low blood volume shock and as much as 40 percent before it dies. Dying from loss of blood is not very common with horses. Make the area safer, if possible, remove any entanglement, and wait until the horse calms down. A horse with a serious wound will generally calm down in a short time to where treatment will be possible. When it does calm down you can minimize movement by tying up the horse, movement which may make the injury worse.

Many riders are attached to their horses and witnessing their companions bleeding or in distress can send one into a fit equal to or greater than that of the horse, and that is exactly what your horse does not need. I have a rule on the trail that my family understands clearly – no matter what happens on the trail – stay calm. I mean it and they know it. The horse needs you to make clear sensible decisions and you need to be in a state of mind to do so. And if you fly off the handle or fall to the ground in a wave of tears, your excitement and distress will get the horse(s) and those around you even more excited and distressed.

Knowing the vital signs can help evaluate the distress level the horse is in and help your peace of mind in times of trauma. If you discuss the injury with a vet, they may ask for the vital signs. The pulse rate should be about 30 to 40 beats per minute at rest. Greater than 60 beats are irregular. Pulse rate can be taken on the artery just under the cheek bone. Body temperature is taken with a lubricated thermometer in the anus and should be 99.5 to 101 degrees Fahrenheit (Celsius?). Above 104 is abnormal. Dehydration can be determined by the pinch test or gum test. Pinch the skin on the neck just above the shoulder. The fold you pinch should disappear as soon as you let go, if you can watch it disappear, while you count one, two, then the horse is dehydrated. You can also press you thumb on the horse’s gum just above the corner incisor and it should take 2 seconds or less for the color to return or the horse is dehydrated.

There have been a few times over the years when a serious injury and an excited horse required a scotch hobble or laying the horse down with a rope before treatment was possible. For trail riders who go on remote trips or travel the back country often, learning a user-friendly way of laying down a horse with a rope is a good idea.

Do a quick assessment of the horse for broken bones, injury to the head or eyes, and wounds. First response for wounds on a horse is just about identical to that of a human. If the wound is bleeding badly, or if blood is squirting out, indicating an arterial cut, you need to stop the bleeding with direct pressure, as firm as necessary until bleeding stops. This can be in the form of a balled towel or cloth or your hand if one is not available or until one is available. On a serious wound like this a vet should be called immediately. A vet can provide further instructions until they arrive, administer drugs that will assist recovery, and recommend continued treatment. On the trail, you need to continue with treatment yourself immediately.

Stopping the bleeding may be easier said than done. We had a two-year-old colt trailing behind its mother deep in the Alberta Rockies when it kicked back at the horse behind. Just above the point of the hock it struck the edge of the long-distance bell of the horse behind and cut itself deeply, to the point where the artery was cut. Blood shot out at an alarming rate and distance and the horse was in no frame of mind to let anyone play with its back feet. In a great hurry we laid the horse down and got direct pressure on the wound, unfortunately, the bleeding persisted, it just could not be stopped with direct hand pressure. In a situation like this it is acceptable to apply a tourniquet. A balled-up cloth for a pressure points with an over cloth twisted with a stick insert until the bleeding stopped. I always carry electrical tape on the trail and the small stick was taped in place until we made it into camp fifteen minutes distant.

Tourniquets need to be relieved of their pressure at regular intervals to allow circulation and it was a full day later before we could relieve the pressure of the tourniquet without bleeding. The bleeding was so dramatic that I could not imagine how the foot could survive without the blood flow to keep the foot alive, but here was a great lesson in the vitality of horses – over time secondary arteries can enlarge and take up the needed flow of blood. At the time the recovery seemed a miracle to all of us who witnessed the injury.

Again, treating a wound on a horse is like that of a human; stop bleeding, clean wound, and treat with the appropriate topical, and stitch and/or bandage if appropriate. Clean wounds with clean water and betadine or a saline solution (two tablespoons of salt in a gallon of water). Add betadine to the water until it is the color of light tea. If you do not have betadine or salt available then use water only, clean stream or lake water if nothing else is available. Hosing down is most common but a spray bottle or just splashing the water on the wound will work. A wound should not be hosed down for longer than several minutes. If the exposed tissue begins to turn white you have killed it with excessive hosing.

A sanitary cloth or sterile gauze can be used to lightly clean debris from the wound. Peroxide is also commonly used to clean wounds, particularly punctures, however some vets claim that the action of the peroxide can drive contaminants deeper into the wound and peroxide can kill healthy cells. An iodine solution is often recommended to clean and treat punctures. Due to the aggressive nature of iodine, it may be more effective for deep punctures but that is about the only time we use it, it is not recommended for wounds in general due to its aggressive nature and the damage it can do to cells and the creation of proud flesh.

All puncture wounds should be considered serious as they can result in Tetanus and with a horse that has not been vaccinated tetanus(lockjaw) is a virtual death sentence. The tetanus bacteria are common in the soil and dead debris. I once saw a horse contract tetanus from a small stick the size of a half a pencil that had jabbed and stuck between the foreleg and chest. Unnoticed, it had taken only a week for the horse to go into shock and die.

So now that the wound has stopped bleeding and is clean a topical is generally applied. For upper body wounds that are soft and weep, a spray or dry pray is often used as an ointment will slough and not stick as well. Many who have witnessed large and deep upper body wounds (above the elbow) with exposed flesh from wire cuts and other trauma are amazed twice - once when the vet chooses not to stitch and once when the gaping wound is treated with an appropriate topical and heals surprisingly quickly with little visible damage. One reason that stitching a flesh wound is not overly common is that by the time the vet arrives the wound has been exposed to the elements and is contaminated and better left open so the contaminants can be flushed. Another is that the air helps to heal, partly because of exposure to oxygen.

Lower leg wounds require a different approach. The lower leg has more motion, more tension and less blood circulation under the skin and if left exposed are more likely to collect dirt. They often look less damaging but can take longer to heal and are more likely to require a bandage or stitching. As a rule, once lower leg wounds are cleaned, they are treated with the appropriate salve and wrapped with sterile gauze and a tensor bandage, not so tight as to prevent adequate circulation. If you cannot clip or tie the bandage for some reason, then use electrical tape or ladies hose wear as an outer tie as opposed to duct tape as duct tape is rigid and may create too much pressure. Lower leg wounds should have the bandage removed and fresh dressing and bandages re applied daily. Bandages should remain on the horse until signs of healing – firming and scabbing over – appear. Lower leg wounds are also more likely to grow proud flesh, and a bandage will inhibit proud flesh as well as keep the wound clean and reduce inflammation.

For small wounds and rubs where the skin is not broken at all, maybe a rock or a stick scraped off some hair or maybe the horse has a slight rope burn, no treatment is necessary. For smaller upper body wounds that bleed, they can be flushed or wiped with a clean damp cloth and covered with an appropriate salve or spray. Smaller lower body wounds need to be assessed and if in doubt apply a salve and bandage. Practically speaking, horses that spend time on the trail will often have little ‘owies’ where they clip a sharp stone, or a stick jabs a leg or something and a small trickle of blood appears. It stings for a moment and the horse forgets about it in a short time. If it was a lower leg owie and you did take the time to stop and apply salve, then it would likely be wiped off or washed off with the first grassy meadow or stream or mud puddle. With these smaller wounds I will often treat the horse when we get to camp because the salve or spray is more likely to stay on while the horse feeds and rests for the night. If you do not have any type of salve or spray topical with you then just flush and clean the wound regularly, with salt water if possible. An exposed smaller wound that is kept clean will generally heal just fine with no topical.

Blows to the head are not uncommon with horses as they kick about through the course of their lives, but their skull structure is very dense and protective and deaths from blows are uncommon. Treat a wound to the head and neck area as any wound. However, looking at a head wound may not tell the extent of internal injury. Brain damage can be assessed by the horse’s behavior. A horse that stumbles, has poor balance, shies with sudden movement-like hands being moved, bumps into things, can all be indicative of brain damage. Horses who get concussions can lose consciousness and be out cold for many minutes before coming to, with no apparent ill effect. If a serious concussion or brain damage is suspected a vet should be called and they may prescribe an anti-inflammatory. A horse that is likely to recover from what appears to be brain damage will show dramatic recovery within twenty-four hours.

There are times when you call a vet immediately including when blood spurts and cannot be stopped, when bones are broken, brain damage symptoms occur, a cut, poke or trauma to a joint where a clear or yellowish fluid leaks out or when an eye is poked or otherwise damaged and it begins to take a whitish or cloudy appearance. Even a small cut on a joint is dangerous as the infection can penetrate into the joint or tendon where it is very difficult to treat and can permanently damage or eventually kill the horse – ditto for humans.

Rope burn, rubs and scalds benefit from treatment. Trail riders who pack horses will need to treat these conditions more often than those who do not simply from the fact that they use more horses in challenging terrain, horse loads are wrapped with ropes that may loosen and entangle, and loads are dead weight that rock and sway and are far more inclined to cause rubs, scalds and blisters than a rider. Picket lines and hobbles may also cause rubs. Generally rubs are not serious and often not treated unless the skin is broken but they are more than just a nuisance because if the cinch rub or hobble burn or a blister from a load forms then you are faced with having to continue using the horse without causing further damage or you retire the horse until it recovers which is not a desirable option when you are two days back on a wild ride.

Rope burns and hobble rub often occur in the pastern and fetlock or lower leg area so we always treat a rope burn or hobble rub on the lower leg with a good salve that sticks well, heals well, repels insects and keeps the rubbed area supple. Repelling insects and keeping dirt out of the rub is key. We rarely bandage lower leg rubs while on the trail because the wrappings just do not last on wilderness trail rides and unless it is a very aggressive rub with excessive bleeding and broken skin there is not much advantage to wrapping a rub.

Saddle rubs in the wither area require your attention. It is not the aesthetics of the hair rubbed off that concerns us or the white hair that may show up at a later date, but the fact that swelling may occur from a wither rub and if the swelling enlarges it is a sign of internal infection or fistula, a very aggressive bacteria that takes hold and can get into the vertebrae bone structure, cause considerable damage and even kill the horse. Keep loads off of swollen withers or blisters on the wither until the swelling has gone down and figure out why there was pressure there to begin with, in other words do not place an ill-fitting saddle back on that horse. The problem with serious wither rub while on overnight trips is that if it begins to swell and does not go down over night and it begins to enlarge and gets infected it can require immediate attention. If we discover a rub when we remove a saddle, we usually pour cold water over the area to reduce the heat and damage from heat. Cold water or cold packs are recommended to reduce heat associated with bruising. Then we put on an antiseptic salve. If swelling continues to the point of infection, we administer penicillin immediately and lance the lower edge of the infected area, allow it to drain and get penicillin and betadine right into the infection. This is a job for a vet but again with trail rides that are several days back, not treating the horse is not an option. The point here is not to take a saddle sore/rub on the withers lightly. It is also one of the main reasons we carry penicillin during long trips. When treating fistula wear protective gloves as it can also affect humans.

Understanding topical ointments and sprays and lotions is a science and there are vets that literally specialize in this field. Things were simple in the good old days when you doused fungus with turpentine, mixed it with Vaseline for a salve and made the horse drink it for belly aches. Figuring out what ingredients and which brands to purchase and when and how to use them is a head scratching brain busting blister of a problem. What I do know is that I want my salve to really work – it needs to stick well, heal as quickly as possible, and repel flies. Personally, and this is just my old-fashioned opinion handed down from years of fixing horse owies, I do not really care if my topical treatments have organic this or that or the latest wonder ingredient. I just really need it to work. One of the reasons that home remedies are still popular with horse owners is that many of them really do work and they are often cost effective.

Choosing topicals is a challenge for horse owners. What is on the shelf may say ‘for livestock, horses, etc.’ but as far as a certain vet may be concerned it is too aggressive or should not be used for one reason or another. Testimonials from vets and horse owners are just as confusing. One person will claim a product works wonders, and another will say absolutely not. One vet made a good point when he said that 60 to 70 percent of any treatment provided, even cleaning the wound with a saline solution, will aid with wound healing. The point being that wounds need to be treated and just do the best job you can. Here are some thoughts on topicals and I would encourage those interested to do some web searches to form your own opinions. Doctor Jolly and his Step Ahead Farm site is an excellent place to start. You should wear gloves when applying any topical solution.

Most topicals are antiseptic and anti-bacterial as bacteria inhibit healing. Eighty percent of all topicals have agents to reduce the formation of proud flesh (tissue granulation) a Catch 22 as these agents typically reduce circulation which is critical in wound healing. Ointments aid in keeping contaminants out of the wound and can help trap blood – the platelets, serum, white blood cells needed in the wound area for healing. Furacin(nitrofurazone)based topicals (often a yellow color) kill a wide spectrum of bacteria but some consider it to actually slow the healing process, some claim by twenty five percent. Personally, we have used furacin extensively over the years and find it to be effective. Purple and violet blue sprays are good for wounds but considered too aggressive (cell damage) by many. Again, we and many others will travel in the back country with these ‘dry’ sprays and use them effectively for open flesh wounds, along with regular flushing. Vet recommended topical agents including Eclipse, Lacerum, silver sulfadiazine (often with aloe vera), Vetmycin and Quick-Derm are a few of the products that have proven very effective. Many come in spray form for upper body wounds and cleaning, or salves.

Provadine-iodine (not tincture of iodine) diluted to the color of light tea, betadine(10%iodine with antifungal soap) diluted to the color of tea, saline solution(the equivalent salt percentage as blood), and chlorhexidine are acceptable solutions to flush and clean open wounds. Plain water and hydrogen peroxide are acceptable, but both kill live tissue if used excessively. The trick here is to use water or salt water to flush with modest pressure but quit in a few minutes after the cleaning is done. Pure iodine should never be used on an open wound but does kill bacteria and viruses very effectively and is often used for sole punctures because it is aggressive, albeit harsh. As an anti-bacterial spray, some vets claim it is more effective to spray a wound with 5ml of penicillin then it is to inject 25ml of penicillin into the muscle. As with fistula, applying penicillin directly to a wound, as well as injections, when in a remote location has proven effective.

I am a believer in home remedies because many of them work. I think one of the main complaints against them by a pro would be that some may be harsh, but they were always a bottom-line necessity – the bottom line is that ranchers, farmers, outfitters, need something that works and is relatively cheap. I believe in the effectiveness of pine tar as an antiseptic, a healing agent and bug repellent. It is the base for many home remedies. A mixture of 40% pine tar, 40% petroleum jelly, 20% citron (we blend orange or grapefruit peels then cook it with canola oil then strain it), makes a great home-made bug repellant. Creolin is an aggressive disinfectant/insecticide that is found in hardware and feed stores. It is not recommended by vets for use on wounds, but farmers have used it for decades to paint fence rails to prevent horses from chewing and for coating cuts during castration. Some put in a small amount, 10%, in the above bug repellent recipe to make it a very effective bug repellant.

Ichthammol is a sticky coal derivative and reduces inflammation, draws out infection – from hoof punctures for example – kills germs and soothes pain. Kopper Kare or Koppertox (copper napthanate) is also considered overly aggressive by some vets, but the bottle says for horses and other livestock. It is very, very effective with any fungus including rain rot, hoof rot, and ring worm. Turpentine for sores that won’t heal or fungus - this may be somewhat harsh so if you plan to go this route use Scarlet Oil as it has a pine and eucalyptus oil base. Iodine mixed with sugar to a paste for wounds or fungus. Muscle linament for wounds. I am not about to recommend any of these home recipes, except for the pine tar, but I find them interesting, and a person could easily write an article about home remedies for horses that horse owners have found effective over the years.

Flus are common with horses as they are with humans, and treatment is much the same, excluding Gramma’s chicken noodle soup. Flus are viral as opposed to bacterial and since there are no practical treatments to kill viruses, they are generally allowed to run their course and rarely fatal. Symptoms of equine influenza are also like human flu with a fever and a clear leaky discharge from the nose. In several days the discharge may turn cloudy and a cough may develop. The horse will generally experience depression and lose appetite and drink less. There are a few different flu viruses with the equine influenza virus causing more of a clear nasal discharge and a herpes virus causing a cloudy nasal discharge. Horses with the flu need to be rested with good food and water. It can only help to give these horses some vitamin/mineral supplement.

Treating with Bute can be effective in reducing the aches and pains of the flu, reducing depression and stimulating appetite. For trail riders it is important to take the horse out of a working environment and to a sheltered area and allow rest. When on the trail, even on remote trips, we give a horse with a leaky nose, cough, and depressed demeanor, immediate time off. In other words, pull them off that trail ride until later or use a different horse. The flu generally runs its course in one to two weeks. It is important not to confuse the flu with Strangles.

Horses with strangles, also known as distemper, may also show signs of nasal discharge, fever, depression and lack of appetite. With strangles the nasal discharge is generally heavier and the fever is not as high – 102 to 104. But the condition much more serious as it is very contagious with a death rate of about 1 percent. Strangles is a Streptococcus bacterium that can be effectively treated in its early stages with penicillin. However, many feel that once the swollen glands under the neck (throat latch area) appear and abscess and begin to drain, that penicillin should not be used. At this point the bacteria can spread through the lymph gland system, called bastard strangles, with a higher mortality rate. Infected abscesses that are draining can be successfully treated with providine-iodine (betadine) directly in the opened area.

Strangles can have complications of asphyxia from the swelling, pneumonia, and it may be chronic, returning time and again. Many horse owners with years of experience will tell you that if a young horse gets the bacteria, it runs the course with less damage and trauma but if an older horse gets it there is a greater likelihood of complications and death, possibly due to a less vigorous immune system. Horses with strangles should be isolated for six weeks after symptoms subside.

Here’s hoping you and your horse never need to know what you just learned! Enjoy the spring season and get those itchy feet into your stirrups!

HAPPY TRAILS!

Our first aid kit for trips longer than a couple days included a disinfectant healing spray for flesh wounds, a salve for leg wounds, rope burn and scalds, penicillin for all serious wounds, punctures, as well as swelling with possible fistula. For sprains, one of the more common trail riding ailments, we carried a couple tensor bandages. After the pastern and ankle were completely cooled, we would wrap a tensor bandage around the pastern and ankle, split a flat splint for both sides of the injury and wrap again with the second tensor bandage – not overly tight as to cut off circulation. Off and on we would take blood stop powder. It does work for serious cuts but requires a compression bandage as well.

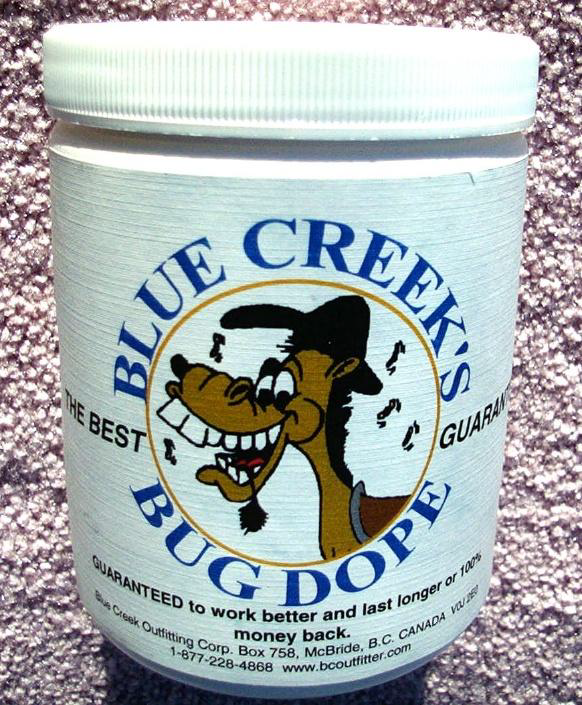

One may not consider a good bug dope as a first aid item, but it can be. At times when bug bites are overwhelming, often from small blackflies that crawl into chest hair, armpit hair, and the groin area, they can create a bloody mess, with scabbing. In the cinch area the sores end up under the cinch, not a nice situation. Furthermore, keeping bugs away from healing wounds is a primary concern. Our bug dope with pine tar and petroleum jelly, as well as other ingredients, was also and excellent healing agent.