CONFORMATION OF THE TRAIL HORSE

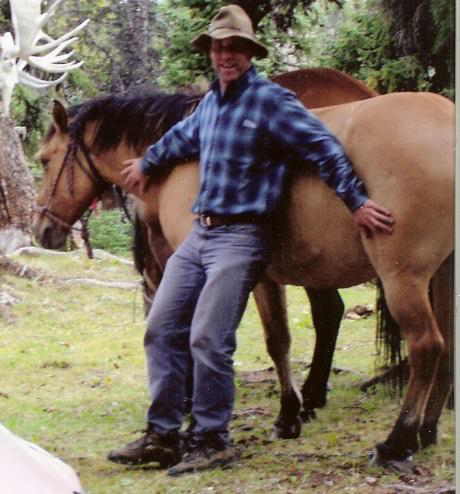

Brass, a pure morgan that had it all, including a long life.

CONFORMATION OF THE

TRAIL HORSE

There was a time, a few middle years during the metamorphosis of our Blue Creek horse farm, when I would not have an ugly horse on the place. We had already gone through our early phase where if a horse had four legs and got me past the first row of trees then it was a trail horse and would do to take me over the mountain. Once that delusion cleared up, I got the idea that there was money to be made selling pure-bred horses, if we were going to feed a horse anyway it may as well be a pure bred.

We settled on Morgans, and I am still glad for that, but even with forty pure bred, sturdy Morgans on the place, I had to finally admit that the nay sayers where right when they warned me about the foolish idea of making a living selling pure bred horses. And it was during these years that we fell into the common notion that our horses had to look better than the next guys if they were going to sell – swan necks, sweet eyes, lips to kiss, and dance like a princess. So, we did not have an ugly horse on the place, until my fence riding halted and I fell down on the side of the wilderness – bush horses, trail horses, wilderness travel, what many of us love to do. Slowly but surely our horses got uglier, and now I worry that they might be too ugly – but then I have heard that there are those that love their mules.

The point here is that with all of this horse experience behind us we were looking for certain qualities, the horses did not get uglier by accident, looks were simply not on the top four wanted list. When you are out there on the trails, navigating timber, mud, streams, needing a friend to calmly stand by you and be there for you when you go to catch, saddle, trim, shoe, feed and tell your stories too, then it becomes clear that beauty really is in the eye of the beholder. It’s like the song, ‘…….if you want to be happy for the rest of your life, never make a pretty woman (man) your wife, if you want to be happy for the rest of your years, put a paper bag over her(his) ears…’

Seriously, as a trail rider, and as I get older, I have an aversion, a mild repulsion, when I see a really attractive or a high energy, blooded horse, particularly one that I was thinking of using as a trail horse. It’s not that a pretty horse cannot make a good trail horse, I am sure that it happens, it just has not happened very often to me, so I have become gun shy.

So, the question remains what do we look for in a trail horse conformation? There are several aspects we consider, not the least being the quality of the foot, but because the foot has been the topic of discussion in the past, let’s give it a rest. Let’s talk about bone. If you have been reading my stuff from the past you will know that I flog good bone like a politician flogs the budget. From an outfitter or a back country trail riders' point of view, bigger bone is generally a good thing. This is because riding over rough, rocky, muddy, ground, with loads that can often be heavier than anticipated, can be a punishing activity. Along with bigger bone comes bigger joints and tendons, and joint problems in a horse - serious sprains and shoulder problems, are more often the result of tendon issues than bone issues. Because of these variables, I am convinced that the longevity of a trail horse is directly related to the quality of bone, joint and tendon.

Obviously, a pint-sized sprout or a rider that reaches up to swipe their debit card at Wal-Mart does not put the strain on a horse that a big person does, so a child riding a draft cross for a trail horse would be overkill, unless, again, the horse doubles as an adult’s riding horse or a pack horse. And terrain is not created equal. If riding is primarily near home, on farmland, or in forest and grassland, there is far less chance for strains and injury then riding up a rocky mountain stream and over the pass. You need to be the judge of the kind of use that your horse will be subject to too, just keep in mind that a horse may change hands a few times during its life. As a breeder I like to breed on the side of caution – bigger bone.

But the size of bone is not everything, riders often wonder if the breed of the horse or the design of the leg can affect durability. There is no question in my mind that this is so. Many times I have ridden a horse one day with a medium to stout pastern with less slope, the type you might associate with a draft, pony breed, or even some Quarter horses, Arabians, or Morgans and others, and the next day rode a horse with the long, highly sloped pastern that you may associate with a Thoroughbred or others. And there is a notable difference, both with how the horse handles itself in difficult terrain and the strain that you are putting on that lower leg in rocky, foot wrenching ground. Although the highly sloped, longer pastern may offer smoother riding and more comfort, I do not believe they are as durable as a stout pastern with less slope. You will generally notice less stumbling about with a stout pastern. But again, depending on the type of riding you do you may appreciate the smoother ride of your Thoroughbred or Standardbred.

Some experienced horse people believe that some breeds offer tougher joints and bone, simply by the fact that they belong to a particular breed. Some feel that you can look at the angles of bone on a leg as compared to the roundness of bone and tell which is more durable. There may be something to this when you consider the history of breeding. For example, proponents of the Morgan horse will tell you that the horse has a tough leg and foot from the many years of breeding for use as a carriage and a pulling horse, whereas the Quarter horse is the flexible athlete of the horse world but less attention has been given to the toughness of the leg. Horse vets have told me that, per capita, they see many more Thoroughbreds and Quarter horses with foot and leg problems then they do Arabs or Morgans, and although I have owned wonderful trail horses from all of these breeds, in this case I tend to believe what I hear. There is good logic and experience when serious wilderness riders and outfitters insist in some draft blood in their trail horses, often Percheron.

Let’s consider the coupling on a horse - the length of the back. I do not believe that there is any real benefit from having a horse that it overly short coupled or long backed. Long backed horses tend to develop sway back (and high withers) earlier than shorter backed horses and generally do not keep their weight as well as shorter backed horses. I feel they do not navigate the tough stuff as well as a shorter backed horse, similar to a shorter base 4wd as compares with a very long wheel based 4wd. With an overly short backed horse and a large rider with a 16 or 17 inch seat, the saddle nearly comes to the rear quarters. This is not the best position for a rider to have on a horse. You also hear comments about the damage that may happen to kidneys with a shorter backed horse because the weight is further back, or kidney damage from overloading saddle bags with a shorter horse. Although it is never a good idea to overload saddle bags, for a few reasons, I have personally never had a horse experience kidney damage because it was shorter backed, and we have had many of them. We have had horses with a tender back from use, maybe a large rider and maybe the saddle did not fit right, but I would guess that back problems would be just as prevalent with a long back as a short one. Shorter backed horses, on average, may not be as smooth to ride, but you really need to try the ride and compare because smoothness has to do with other reasons besides the length of back, like natural gait, shoulder slope and size relative to the hind quarters, the pasterns, and, once in a while, a horse defies all odds when it look like a genuine jeep but rides like a caddy, and vice versa.

You really should consider the withers on your prospective trail horse. I have gone through the same experience as many of you when owning a good horse with high withers made it necessary to spend extra effort to find a saddle with a high gullet, and ‘pad up’ safely with thicker padding and cut outs in the wither area. Personally, I do not like the experience and do not want to be bothered with the extra effort. Over the years we have bred horses with good average withers and bought saddles to suit the majority. Often, very high withered horses have not been the best choice for us because they were, or should have been, in their retirement years, or they belonged to a leaner, blooded horse, which was not the best choice for a trail horse to begin with.

Conversely, a mutton withered horse, a horse with little or no withers, can be a real problem for trail riders simply because there is not enough there to secure the saddle or the load. On the trail you are balancing, flexing, and jostling in all directions, and you and your horse both need a saddle that fits properly and reduces the motion between you and your horse. A flat backed, low withered horse exaggerates that motion, even if it is a wide treed saddle designed for a flat backed horse. How many riders through the years do you think have slid, skid, and bounced on to the ground because the saddle turned on a flat-backed horse?

Some horses are famous for saddles, and riders, sliding over their necks when saddles move forward as they ride downhill. A low withered horse has little to stop this motion. We have a faithful packhorse, Danny, who, when it’s time, which is his decision, somehow encourages his entire load to slide over his neck and head, plop, on the ground, then he stands patiently waiting for help with the load over his head like an ostrich with its head buried in the sand. One time in deep wilds we got to camp and there was no Danny, he had snuck off the trail somewhere. After two hours of riding up and down a long steep ridge I began to look for tracks that might have stepped off the trail and into mossy ground timber. I found him, legs wrapped in ropes and his head and neck pressed down under the pad, packsaddle, and pack boxes, patiently waiting for daddy to find him and set him free. He had been standing like that for at least 2 hours.

A britchn’ or a crouper would solve the problem but sometimes months go by, and he fools us into thinking he does not need one. So when you consider saddles slipping, being able to use a saddle with a common Quarter horse tree, being able to use that horse as a packhorse, a situation where you need stability for your pack saddle or you may sore the horse, you need some withers. Sometimes horses with little wither are simply too fat. With an effort to control feed, and after using the horse regularly, you may find surprisingly good withers in a few weeks. If we need to trim fat from withers early in the season, we will often ride a flat withered horse until the withers show, then pack it. A rider will flow with the motion and keep the saddle balanced, where as a pack is dead weight. Dead wight and a mutton withered horse is a recipe for scalds and worse.

You might think that with a desire for bigger bone we have a hankering for big muscle, but a trail horse does not need the big bunchy muscle that an athletic quarter horse does for quick stops, turns, and bursts of speed. We like muscle, but do not need big bunches of it on the rear quarters, it really is just extra weight and probably not the best type of muscle for long days on the trail. There are several breeds of horses including Arabians, Walkers and Morgans, that have leaner muscle that is well suited to long days on the trail. However, because we need power as well as longevity, power to push up steep slopes, through mud, jump up banks, stabilize loads in swift water, we like to see good muscle, particularly in the upper leg area, the gascon and stifle.

The size of your trail horse is mostly personal. Some like the feel of riding a tall horse and some prefer to be closer to the ground. Personally, I like the sway of a taller, smooth riding horse, particularly during long days. Over the years, if I had to make long miles over a long day, I would choose a tall horse. But I do not like to have to search for a stump just to get on one, or to have 4 big horses take up room for 6 in my horse trailer or have to pack a 17 hand horse day in and day out, so, like many, I commonly ride a sturdy horse 14.3 to 16 hands. You can choose to use a double diamond to hitch your pack horse, so you do not have to reach up impossibly high and tie off, but still, a sturdy 15 hand packhorse is more user friendly than a 17 hand one for the average Joe.

If you cross many streams and rivers, a tall sturdy horse has a definite advantage by having less water push against its sides, catching the belly, and being more adept at navigating slippery, big, stream boulders. You should always take kids off of ponies when crossing streams and place them on sturdy full-size horses, behind the saddle seat with an adult if needed.

I would venture to say that in the long run an average sized horse is safer than a tall one for daily use and pack trips as you have to mount and dismount in a hurry at times, and sometimes seconds can make a difference.

Many horse riders who have leanings toward the performance disciplines are conscious of the quick, catty advantages of a long neck and fine poll, and may relate that need to a soft turning trail horse. Although it would not be a disadvantage to have a fine poll on a trail horse, trail conditions do not really demand a fine poll. You’re turning left and right and back and over are a matter of a soft mind rather than a fine polI. I clearly remember the softest, easiest turning, horse that I have ever owned. It was a very stout necked Fjord gelding that I purchased from a Lady in Smithers, B.C. This horse was a thing of beauty, a Porche in a Fargo body. It made me a believer in the art of groundwork and the truism ‘you can’t judge a book by its cover.’

When we look at the idea of body conformation faults, we find controversy because what may be a conformation fault in a racehorse may not be in a driving horse or a work horse. Let’s look at some conformation faults that may concern trail riders. We already touched on a long sway back being a weaker back and long sloping pasterns being smooth riding but not as strong for rugged trail riding, and both are what I would personally consider conformation faults when taken to excess. You often see pictures of imperfect horses and one of the imperfections that stand out is a ewe neck, a neck that dips as it leaves the shoulders. I do not feel that a slight ewe neck would have much bearing on your trail horse, but the slope of you shoulder may. A well sloped shoulder, as common with many quarter horses, is generally smoother to ride than an upright shoulder, as seen with high stepping horses. A neck that comes up high off of the front end may look pretty but many trail riders have been whacked in the face by an upright neck or head that came up quickly, the rider caught off guard. I have earned an eye watering pain full whack myself a few times and not always with a high headed horse.

A roach backed trail horse, a back that bows up, opposite to a swaybacked horse, may be more difficult to fit a saddle too and therefore more susceptible to back problems in some situations. I believe there may be truth to the concept that a small chested horse does not have as much room for heart and lungs and therefore is not as good an athlete as a horse with a deep or well sprung chest. Personally, I like to see a medium or wider chest on my trail horses both for the idea of better wind and possibly a wider wheelbase being better in the rough stuff. However, an overly wide chest that has narrow based feet, feet that come close together on the ground, narrower than the chest, is fault to watch for. Mules seem to be at odds with my thoughts on the chest because they are often narrower in the chest but generally very sure footed, however, as narrow as they are the chest, they often make up for it by being very deep.

I would also consider front legs that are back-at-the-knees, knees that back under the forelimb, a weakness and a fault for a trail horse. I am not sure that a horse that is slightly toe in or toe out is a serious fault, however if the horse swings its feet out noticeably or is noticeably pigeon toe then it cannot be a good thing for stability under trail conditions. Cow hocked is another term some use to describe a fault, but many cold-blooded draft horses are somewhat cow hocked and I do not believe it makes them less sure footed on the trail – within reason.

Wry foot is a hoof wall that is not symmetrical. Often the side wall between the toe and the heel comes in, to the point where it has a rolled under look. This can be genetic or from a lack of proper trimming. I have one horse with wry foot and it is an extra effort to trim this horse properly and shoe it, but if you plan to ride a wry footed horse you need to give it the extra attention if it is to be a useful trail horse.

Well, I hope you enjoyed the article and that it is some food for thought. Please consider the conformation, strength and hardiness of what a trail horse needs to be, its own strengths for the trails and trials of its own life, its value unto itself, rather than what you like to see in terms of looks or movement that may be novelty to satisfy yourself.

No horse is perfect. If your horse is friendly, reliable, a great partner, and a joy to ride, well, you can still enjoy your trail ride even with some conformation faults as described above.

Happy Trails!

Most breeds have some strains and individuals who will make great trail horses. However, because of the importance of a calm mind and good bone and thicker hoof walls, we were able to breed good trail horses for 30 years only because of the cold blood, or draft – mostly Fjord and Percheron, that we cross bred with our morgans. Junior, pictured above, was a pure blood quarter horse and one of our best horses ever. He was exceptional in all the desired qualities in the article.

I am often asked, what's more important in a good trail horse, the mind or the conformation. I use to say they a about equal. But no more. If you have a friendly, calm, forgiving horse, without the desired build, as explained in this article, you can still enjoy trail riding - within reason. But long days and difficult terrain under heavy loads demand more from our horses.

Long backed horses may develop issues like sway back as they get older. The Polish Limousinsky is an exception, and room for the whole family!