THE ART OF WRANGLING

THE ART OF WRANGLING

Wrangling means working with horses on the trail or in camp, including when they are not being ridden or packed. This means bringing them in during the morning, turning them out at night, and managing their movement and use. It is possible that if you ride out from your yard, or if you trailer your horse to the trail head and ride back to the trailer each day, that you may never get to know wrangling very well at all. For those of us who travel long distances overnight, or who travel long distances and need to turn horses out overnight in unfenced areas, wrangling becomes a necessary chore. And it can be much more than just a chore. It may be more like trail ridings’ evil brother; you are stuck with it, but you really would rather have nothing to do with it. Horses get tangled in ropes, hobble rubbed, make you get up in the wee hours and work overtime, get lost, and need to be dug out of hidey holes you didn’t know existed.

Like most things in life the decisions that you make will greatly affect the outcome, and making good decisions with wrangling gear and strategy can at least make wrangling bearable. Calling wrangling an art might be a stretch but as the years go by the little tricks and techniques that you learn certainly make it feel artful. Let’s look at wrangling gear first.

Hobbles are the primary tool for temporary or overnight feeding. Hobbles can be narrow between the sleeves, narrower than six inches, or wide, up to fourteen inches between the sleeves. Narrow hobbles are often called standing hobbles, used to train the horses to stand, sometimes for the purpose of breeding. Feeding hobbles need to be wider, typically 10 to 14 inches. 14 inches for draft type horses with a longer stride or sometimes the preferred width if outfitters actually want their horses to cover more ground if feed is scarce. If feeding hobbles are too narrow the horse will have to jump forward to keep feeding rather than taking small steps. This can cause the horse to cover more ground and be further from camp in the morning, and also the pastern area is more likely to rub with less width. However, some rubbing can be expected for learning horses. How much a horse gets a hobble rub really depends how quickly it learns to accept the hobble, how soon it stops ‘fighting’ the hobble, and what material the collars are made from.

You would think that you could call a horse dumb or smart depending on how fast it learns to take small steps rather than hitting the end of each step but that is not the case. We have very intelligent horses that need to re-learn hobbles each year, after ten years of using them, and they seem to fuss with them all season. Most calm-minded horses struggle with the first few steps and inside of five minutes act as if they have had them on their entire life. I would agree with many old timers that some horses that are stubborn learners, and who experience some degree of hobble rub, need the uncomfortable feeling of a rub to teach them to stay off of the hobbles and walk gently. Carry a medicated ointment to apply on hobble rubs.

Using a forgiving material around the collar for first time horses is important but it seems about two horses in a dozen will push it enough to get a rub no matter what. Give the horse a good start by using a soft rope, about eighteen inches between the collars, the first time. Use a bowline knot around each pastern and it can be easily removed. Placing the hobble above the ankle is a good alternative and it can reduce rubbing. The first few times you use hobbles on a horse place use them for short periods, say an hour or so, until they get used to them.

Hobbles are often not enough, and I have written stories about adventures while retrieving horses that hopped away, as much as twenty miles away, over a long night. We consider a sideline, tie down, and hobbles on the back feet, useable alternatives. A sideline is simply an additional hobble from a front foot to a back foot. It allows the horse to walk as it feeds but not to run. We use them extensively and have found them safe and very effective. Again, the horse often needs some time to accept them. For your average 1100-pound quarter horse we find about 28 inches between the front and back foot is about right. Again, some horses will get used to a sideline in minutes, and others, never. It takes some time so watch the horse carefully the first few times and do not leave them on too long without checking for rubs. You would think that a sideline would get stuck on brush and deadfall, but I have, over 25 years, only had a horse get caught up twice that I can remember – and this is with 6 to 16 horses turned out each night.

Some riders prefer to tie the horse’s head low to one foot, so that the head is about level with its back, as well as having hobbles on, as a method of keeping the horse from running off. You see this watching cowboy movies when out on the range the cowboy wraps both reins around the pastern and turns the horse out to feed while they have a break. It works well. It used to bother me to see a horse stand around all day with its head down, until I learned that a horse standing with its head lowered is a naturally relaxed position. It lowers the heart rate. And, we have found that a horse spending time this way becomes more forgiving when placing on halters and bridles etc.

Hobbles on the back feet are excellent if your horse can get used to them. They can truly be effective in preventing a horse from running off. However, some horses never learn to accept them, and they just stand still or repeatedly crash off looking for an accident. For some reason our Fjord crosses have no problem with back hobbles but our Morgans and Percherons struggle in them. This method has been great for us on those rare trips when the snow is deep enough that horses need to paw for feed.

As a final note about hobbles, they can be viewed by some as cruel, after all, who wants to be shackled all day. But relatively speaking, a horse prefers being hobbled in an open field, feeding and lounging about, rather than being tied on a tether rope, on a high line, tied to a post or a tree, confined to a stall or a small corral, or at times even being ridden. How do I know? Just watch their mannerisms when turned out with hobbles in a grassy meadow. They roll, shake themselves, head out munching and forget they even have hobbles on.

A picket rope is a soft three-quarter inch or larger rope, twenty to fifty feet long, attached to a tree, post, or peg on one end and the horse’s foot on the other. It should have a swivel on the foot collar and be able to slide freely around the tree or post. A bowline knot will keep the post end from tightening and be undone later. We find that attaching the rope to a foot far safer than the halter as the horse is more likely to become tangled and possibly choked when tied to the halter. I realize that many riders successfully tie picket lines to their horse’s halters for feeding but once I left a big palomino gelding to feed in a pretty mountain meadow for a few hours and arrived to find him down and tangled. Once was enough. We never leave a horse unattended while on a picket line for more than an hour or so, and never overnight.

Be sure that there are no obstructions or brush for the horse to get tangled in and enough feed to keep him well fed. Riders often picket the dominant horses or the ones that like toto order to keep all horses close but rotate your picket horses so they all have a chance to free graze.

Always walk your horse to the end of the picket line before letting them go. We find the back foot safer than the front foot but it takes some getting used to. You can tug on the rope tied to the back foot to get it used to the feel.

High lines are an effective way to control and feed horses. Tie the high line above the height of the horse’s head and long enough that the horse can eat the hay or feed provided, but short enough that they cannot get a leg over the lead rope. We use an inline bowline (See Blue Creek Trail/Packing’ book), or commercial metal fasteners, about eight to ten feet apart for each horse. We Prefer the inline bowline as we do not have to carry heavy metal fasteners, and it's cheaper.

High lines are supposed to be environmentally friendly, but I have witnessed several horses on a highline each night for a week and the ground looked like a hog wallow twenty feet across and eighty feet in length. Every small tree, willow bush, and blade of grass was destroyed. High lines are for hard ground areas only. Tying a horse overnight to a tree is also very destructive and an active horse can completely destroy a good-sized tree in one night. If you are close by, put hobbles on so they cannot destroy the vegetation. We find that tying a horse to a tree for the few minutes it takes to put hobbles on, and free grazing the horse, the friendliest to nature. Government offices and individuals in many areas, including many parks, have decided that horse riders should pack in their feed. These areas are now terribly infested with buttercup, white daisy, thistle, and a host of other terrain eating weeds that came in with the hay. Many grasslands have been ruined by these laws, by the very people who are supposed to protect them. If packing in feed is necessary then it should be pellets or cubes, which generally have fewer weed seeds.

Portable fencing kits are very portable and work great, but be sure to train your horse to the hot wire at home. Put on hobbles even when confined inside a hot wire because horses will ‘crash’ the fence and you could be in for a long walk.

The morning ‘jingle’, when you bring in the horses can be another sort of adventure. Unless you are a well-honed wrangler with well-honed horses, you need to always control your horses. The more horses free, the more trouble. If you are bringing in a large number, say eight or more, it may be wise to tie all to trees then lead in half, neck tied one horse to another (a good reason to use 10–12-foot leads for back country trips). Sometimes, if not too far from camp, we lead a few of the leaders in and let the others hop in with hobbles on. Again, keep all your horses confined; tied with leads, tied to each other, or still in hobbles. When leading a string of horses keep your ‘bell mare’ or dominant horses up front. We never lay our hobbles on the ground, you can easily lose them in the grass, they are on their feet or wrapped around their necks.

One day while deep in the remote Spatsizi country I roamed helplessly about trying to figure out tracks and where the horses went to. The horse tracks walked out in many directions from camp but eventually the tracks ended. After returning to camp from a fruitless mile walk, tired and distressed, I caught the slight ‘tink’ off a horse bell.

And there, fifty yards from my tent, behind a few big spruce, were the three culprits, watching me with smiles on their faces. Just think, if they did not have bells on that ‘tink’ would not have happened. We now try to have bells on all our horses, not just the bell mare or a few horses.

Tail tying two horses to each other’s tails is a great way to keep horses in one place if there are no trees - alpine or the prairies for example. It is enough reason to learn how to tail tie. There should be no more than 2.5 – 3 feet between the nose and the butt. Leading horses back to camp head to tail is great, we just find that using an 10-to-12-foot lead rope and leading head to neck faster.

Leading packhorses together head to tail is the time-honored tradition but knots can become jammed, tail hair lost, and horses stuck between trees. People can get hurt. A breakaway string behind the packsaddle is better (See Blue Creek’s Trail/Packing Book). Good luck on your overnight trips and may the great wrangling spirit be with you!

Oh, the times guides, wrangles, and trail riders have shared their wrangling frustrations with me about a trip or a season, or shared with joy how things went. Most of the grief or joy boiled down to the training and disposition of their horses. Camp friendly horses can turn wrangling, and life, into an agreeable chore.

These riders are taking chances allowing their horses to free graze without hobbles. The horses only stay put because they just rode 10 miles. They did have the sense to remove bridles.

Good people feel a deep sense of satisfaction when horses they rode and packed all day are happily feeding. Good people go through a lot to make sure they are happily feeding, including walking miles when horses head off to find better feed.

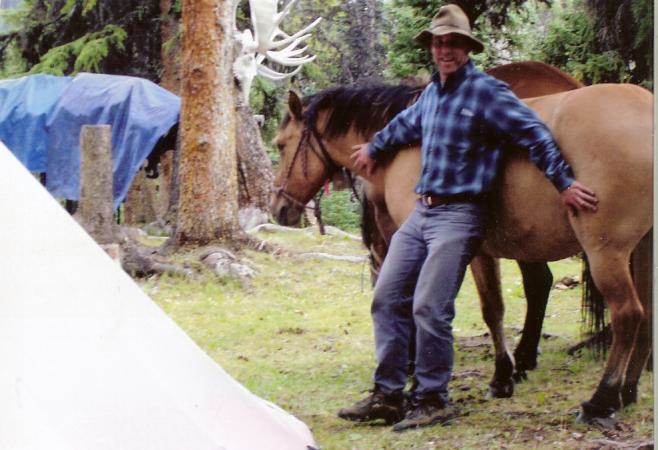

Experienced outfitters have detailed knowledge, habits, and eyes in the back of their heads – little things that make the trip go smoothly, little things that can become big problems. These two wranglers should be leading more horses back to camp tied head to neck or tail, not lead ropes in each hand with other horses free.

Many of those details, tips, and techniques outfitters, guides, and wranglers gain from years of experience are yours to learn and practice for your first trips, available through books, video, and clinics. I have seen many first-time packers with their outfit looking sharp and tight, and many experienced groups look sloppy.